Li Shizhen (Li Shizhen), courtesy name Dongbi, was born in 1518 in Wuxiaoba, Qizhou, Hubei Province. Li Shizhen came from a family of physicians with three generations of medical practice. His grandfather was a doctor, and his father, Li Yanwen (also known as Li Yuechi), was a well-known local physician who served as a “Taiyi Li Mu” (a high-ranking imperial physician). He not only had rich clinical experience but also possessed considerable theoretical knowledge in medicine. Later, Li Shizhen praised his father’s diagnostic knowledge as “profound and subtle, beyond the reach of shallow learning.” It is recorded that Li Yanwen authored works such as “Four Diagnostic Methods” (Si Zhen Fa Ming), “Aiye Chuan” (Transmission of Mugwort Leaves), “Ren Shen Chuan” (Transmission of Ginseng), and “Variola Zhen Zhi” (Diagnosis and Treatment of Smallpox). Li Shizhen was nurtured in such an environment from a young age.

Content of the Book

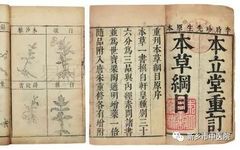

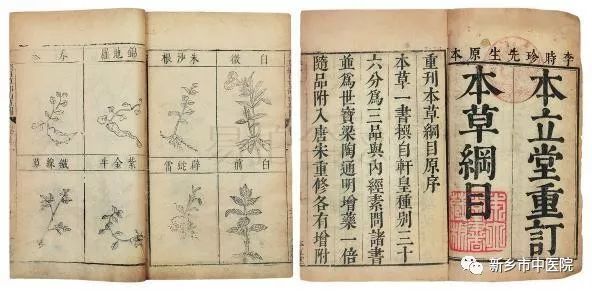

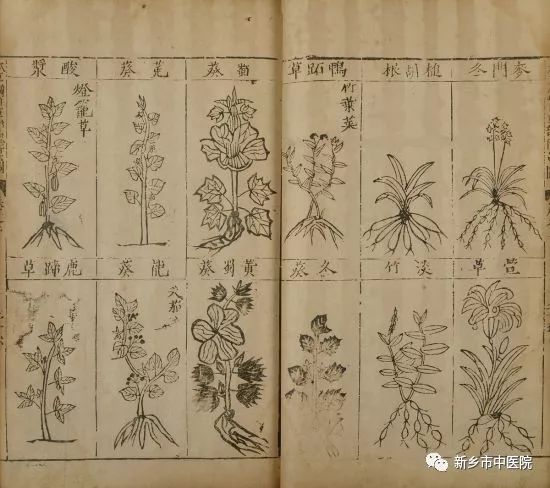

The “Compendium of Materia Medica” (Bencao Gangmu) consists of 52 volumes, documenting 1,892 types of medicinal substances, including 374 new drugs, and collecting 11,096 medical prescriptions. The book also features 1,111 exquisite illustrations and approximately 1.9 million words, divided into 16 sections and 60 categories. Each medicinal substance is categorized with sections for name clarification (determining the name), collection (describing the origin), corrections (correcting past literature errors), preparation methods, properties, indications, and inventions (the first three items analyze the functions of the substances), as well as supplementary prescriptions (collecting folk remedies). The book includes 881 types of plant medicines, 61 types of appendices, totaling 942 types, along with 153 unnamed plants, making a total of 1,095 types, which account for 58% of all medicinal substances. Li Shizhen classified plants into five categories: herbs, grains, vegetables, fruits, and trees, further dividing herbs into nine subcategories: mountain herbs, fragrant herbs, wet herbs, poisonous herbs, climbing herbs, aquatic herbs, stone herbs, moss herbs, and miscellaneous herbs. This work is a precious heritage in the treasure trove of Chinese medicine, serving as a systematic summary of TCM before the 16th century, and is hailed as the “Great Classic of Eastern Medicine,” having a significant impact on modern science.

The “Compendium of Materia Medica” changed the original classification method of upper, middle, and lower grades, adopting a scientific classification of “analyzing families and categories, and dividing sections and items.” It categorizes medicinal substances into mineral medicines, plant medicines, and animal medicines. Mineral medicines are further divided into four categories: metals, jades, stones, and salts. Plant medicines are classified into five categories based on their properties, morphology, and growth environment: herbs, grains, vegetables, fruits, and trees; the herb category is further divided into mountain herbs, fragrant herbs, awakening herbs, poisonous herbs, aquatic herbs, climbing herbs, and stone herbs. Animal medicines are arranged in order of evolution from lower to higher, divided into six categories: insects, scales, shells, birds, beasts, and humans. There is also a category for utensils. This classification method transitioned to a system based on natural evolution, from inorganic to organic, from simple to complex, and from lower to higher. This classification was quite advanced for its time, especially the scientific classification of plants, which predates the work of Swedish taxonomist Carl Linnaeus by 200 years.

The “Compendium of Materia Medica” not only achieved great success in pharmacology but also made outstanding contributions in chemistry, geology, and astronomy. It recorded a series of chemical reactions involving pure metals, metal chlorides, sulfides, and more, and documented modern chemical operations such as distillation, crystallization, sublimation, precipitation, and drying. Li Shizhen also pointed out that the moon, like the earth, is a celestial body with mountains and rivers, stating, “I dare say the moon is the yin spirit, and those who dance upon it are the shadows of mountains and rivers.” The “Compendium of Materia Medica” is not only a monumental work in pharmacology but also a true encyclopedia of ancient China. As noted by Li Jianyuan in his commentary on the “Compendium of Materia Medica”: “From ancient texts to legends, everything related is collected, and although it is called a medical book, it actually encompasses the natural sciences.”

Influence of the Book

The “Compendium of Materia Medica” improved traditional Chinese classification methods, with a relatively uniform format and a more scientific and precise narrative. For example, it expanded the broad category of “insect” medicines to 106 types, with 73 types of insect medicines divided into three categories: “oviparous,” “metamorphic,” and “moist-born.” This has significant implications for the development of taxonomy in animals and plants.

The “Compendium of Materia Medica” corrected many errors from previous works, such as the misidentification of Nanxing and Huzhang as two different substances when they are actually the same. Previously, Wei Rui and Nü Wei were considered the same medicine, but Li Shizhen identified them as two distinct substances. Su Song’s “Illustrated Compendium of Materia Medica” mistakenly classified Tianhua and Kua Lou as two different plants, when in fact they are the same. Previous scholars mistakenly believed that “horse essence enters the ground and transforms into lock yang” and “grass seeds can turn into fish,” all of which were corrected. Additionally, many new medicinal substances were included in this book. For certain substances, Li Shizhen provided further descriptions based on his own experiences. The book also contains a wealth of valuable medical information, including numerous supplementary prescriptions, verified prescriptions, and case studies, as well as useful historical medical materials.

This book is not only a pharmacological work but also a work of natural history with a global impact, covering a wide range of topics in biology, chemistry, astronomy, geography, geology, mining, and even history.

The “Compendium of Materia Medica” is a comprehensive work that encapsulates the achievements of Chinese materia medica before the 16th century. The materials collected in the book are extensive, “from ancient texts to legends, everything related is collected,” thus some content may not align with modern understanding and may even have superstitious elements. For example, lead powder is described as cold and non-toxic, while modern science considers it highly toxic; the book also includes entries such as filial piety clothing and hats, widow’s bed dust, grass shoes, male pubic hair for treating snake bites, female pubic hair for treating “five lin, yin and yang diseases,” human soul (the soul of a person who hanged themselves) for calming fright, human flesh for treating consumption (cutting flesh to treat kin), and human excrement for treating vomiting blood, among others. Li Shizhen mostly cited the views from “Chuo Geng Lu” and “Bencao Shiyi,” adopting a skeptical attitude towards these claims, stating, “All that has been used by people should not be neglected.” Additionally, Li Shizhen refuted Chen Zangqi’s “Bencao Shiyi,” arguing that the idea of eating human flesh to treat consumption is erroneous. However, it is precisely due to the meticulous collection of details that some ancient medical texts and materia medica that have been lost have been preserved through the “Compendium of Materia Medica.”

Publishing Process

After completing the “Compendium of Materia Medica,” Li Shizhen hoped to publish it soon. To resolve the publication issue, the over-70-year-old Li Shizhen traveled from Wuchang to Nanjing, the center of the publishing industry at the time, hoping to solve it through private merchants. Due to years of hard work, Li Shizhen eventually fell ill and instructed his children to present the “Compendium of Materia Medica” to the court in the future, hoping to use the court’s power to disseminate it to the world. Unfortunately, Li Shizhen passed away before seeing the publication of the “Compendium of Materia Medica.” In that year (1593), he had just turned 76.

Shortly thereafter, the Ming Emperor Zhu Xujun ordered that books be submitted to the court from all over the country to enrich the national library. Li Shizhen’s son, Li Jianyuan, presented the “Compendium of Materia Medica” to the court. The court approved with the words “book for review, Ministry of Rites to be informed,” but then set the “Compendium of Materia Medica” aside. Later, under the printing of private publisher Hu Chenglong in Nanjing, the “Compendium of Materia Medica” was published three years after Li Shizhen’s death (1596). In 1603, the “Compendium of Materia Medica” was reprinted in Jiangxi. From then on, it gained widespread circulation in the country. According to incomplete statistics, there are more than thirty editions of the “Compendium of Materia Medica” in China to this day.

In 1606, the “Compendium of Materia Medica” was first introduced to Japan. In 1647, a Polish man named Mikołaj translated the “Compendium of Materia Medica” into Latin for dissemination in Europe, and it was later translated into Japanese, Korean, French, German, English, Russian, and other languages. In 1953, the “Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China” was published, collecting 531 modern drugs and formulations, of which more than 100 were derived from the “Compendium of Materia Medica.”British biologist Charles Darwin referred to the “Compendium of Materia Medica” as the “Encyclopedia of 1596!”

(Content excerpted from the internet)