Follow Famous TCM Formulas to discuss Traditional Chinese Medicine together!

A historical coincidence or mistake often leaves behind irreparable errors, untraceable truths, or perplexing enigmas for future generations…

To Practice Medicine or to Be an Official? That Is the Question

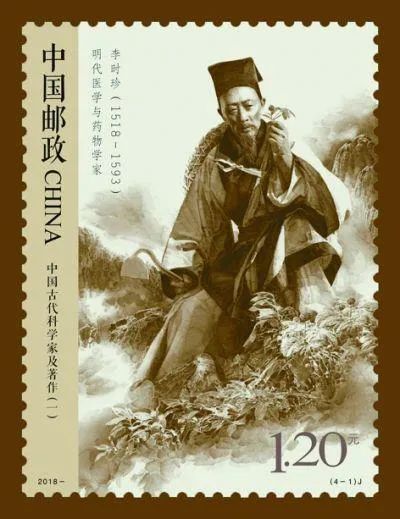

Those familiar with Traditional Chinese Medicine or Chinese history should know about the book “Compendium of Materia Medica” and its author, Li Shizhen. The lost herb we discuss today has a deep connection with Li Shizhen’s “Compendium of Materia Medica,” so our story begins with him… On the 26th day of the fifth lunar month in the 13th year of the Zhengde reign, the weather was fine, and there were no unusual phenomena such as “A white deer enters the house, and purple mushrooms grow in the courtyard”. However, the home of Dr. Li Yanwen in Qizhou Town, Qichun County, Hubei, was filled with joy as his wife, Zhang, successfully gave birth to a son, bringing new hope to the Li family. Facing his son, Li Yanwen placed great expectations on him, entrusting a long-buried dream to the young Shizhen… Li Yanwen’s father, who was also Li Shizhen’s grandfather, was a traveling doctor, similar to today’s barefoot doctors, working hard for little pay and holding a low social status. Growing up watching his father’s struggles, Li Yanwen always wanted to change his family’s fate through education. Unfortunately, he only managed to pass the county-level examination and did not achieve the higher degree, so he inherited his father’s profession and continued practicing medicine. With his status as a scholar and excellent medical skills, Li Yanwen greatly improved his living conditions over the years and gained admiration from local elites, earning a good reputation among the common people. However, he still regretted not being able to become an official. The birth of his son, Li Shizhen, reignited his hopes of realizing that dream, so he did not intend to pass on his medical skills to his son, believing that studying medicine was too arduous and that becoming an official was the proper path. Young Li Shizhen was sent to a private school early on to study the Four Books and Five Classics and to practice writing essays. Historical records state that Li Shizhen “was frail in childhood and grew up with a dull mind”, but he was exceptionally diligent, which led to some academic success. In the 10th year of the Jiajing reign, at the age of fourteen, Li Shizhen passed the county and provincial examinations and was recommended by the governor of Qizhou, Zhou Xun, to take the imperial examination in Huangzhou, where he successfully became a scholar, gaining the qualification to enter Confucian studies. However, it is unclear whether it was due to the misfortune of the Li family or a lack of official career, but Li Shizhen failed the subsequent examinations three times, missing the path to officialdom. After each failure, he would fall seriously ill, facing life and death. Perhaps it was fate; the Li family had a strong connection with Traditional Chinese Medicine. Each failure and illness made Li Shizhen lose hope in an official career while igniting his interest in the medical arts that save lives. After failing the imperial examination for the third time in the 19th year of Jiajing, he decided not to pursue an official career, instead following his family’s tradition and dedicating himself to studying medicine, expressing his determination in poetry: “My body is like a boat against the current, my heart is as hard as iron; I hope my father’s aspirations for me will be fulfilled, and I fear no difficulties until death!” Without the pressure of the imperial examination and the goal of becoming an official, Li Shizhen was finally free to explore various texts, including the Three Canons and Five Classics, and the Hundred Schools of Thought… He read whatever interested him, broadening his knowledge and deepening his understanding of medicine. In the 24th year of Jiajing, a severe drought struck Qizhou, leading to crop failures, followed by floods and rampant epidemics. Under these calamities, the clinic run by the Li family became a bustling place. Li Shizhen assisted his father in saving many patients on the brink of death, and out of compassion for the suffering villagers, he charged no fees and even provided herbs from his own supplies. As a result, the father and son gained the gratitude and admiration of the surrounding communities. This experience made Li Shizhen realize the true value of being a doctor who can help the world. The following year, as if to reward this father and son, Li Yanwen was favored and became a student of the Imperial Academy, fulfilling a long-held dream of his own regarding the imperial examinations. At this time, another dream began to take shape for Li Shizhen…

Three Generations of Authors

During his long clinical practice, Li Shizhen became aware of many errors in the past materia medica compilations, stating: “The number of items is cumbersome, and the names are numerous and mixed. Some items are divided into two or three, while others are confused as one.” Especially concerning many toxic medicines that were mistakenly believed to “prolong life with long-term use”, leading to endless harm. For example, Huang Jing (Rhizoma Polygonati) is a tonic, while Gou Wen (Radix Aconiti) is poisonous; the old materia medica mixed them up, endangering lives. Thus, he was inspired to revise the materia medica, but the sheer volume of materia medica was vast, and historically, most compilations were overseen by the government and funded by the state, taking years to complete. Li Shizhen’s ambition to undertake this monumental task alone shocked his relatives, friends, and fellow villagers. While ideals are abundant, reality is harsh. With an idea in mind, the path to implementation was fraught with difficulty. During this time, due to some opportunities, he cured the son of the Prince of Fushun, gaining recognition from the King of Chu, who appointed him as the chief physician of the royal palace. He later served in the Imperial Medical Institute for over a year but found it difficult to realize his ambitions and resigned due to illness, returning to his hometown.Returning home was one thing, but what to do next left Li Shizhen in confusion. Should he care for his father? Raise a few sons? That seemed too dull. What about the dream of compiling the “Compendium” that lay buried in his heart? He felt frustrated, hesitant, and lost… Days passed in monotony until one day, Li Yanwen called his son to discuss local specialty herbs, reminiscing about the time in the 33rd year of Jiajing when Li Shizhen went up the mountain to catch the white flower snake, a local medicinal herb with high medicinal value. Many people contributed to the tribute of this snake, but local resources were dwindling, and there were often outside merchants passing off inferior products as the Qizhou white flower snake for profit. Upon hearing this, Li Yanwen expressed his regret. To record and fully understand this unique local animal herb, Li Shizhen personally climbed Longfeng Mountain in Qizhou, documenting every detail of the search and capture of the white flower snake, which he later wrote about in “The Tale of the White Flower Snake,” earning his father’s praise. Shortly after discussing the white flower snake, Li Yanwen passed away, leaving Li Shizhen heartbroken.After handling his father’s funeral, Li Shizhen recalled their discussions and investigations about the Qizhou white flower snake, reigniting the dream of the “Compendium” buried deep within him. In the second year after Li Yanwen’s death, Li Shizhen packed his bag, took his son Jian Yuan and his apprentice Pang Xian, and set off on a journey to seek herbs, honoring his father’s spirit in his own way. Perhaps it was fate; shortly after Li Yanwen’s death, his grandson, Li Jianzhong, Li Shizhen’s son, passed the local examination and became a scholar, finally producing a member of the family who succeeded in the imperial examinations. Over the years, Li Shizhen traveled extensively through Hubei, Hunan, Jiangxi, Anhui, and Jiangsu… Wherever he went, he sought out fishermen, woodcutters, farmers, carters, herbalists, and snake catchers as teachers, searching for various herbs, personally tasting and experiencing them. His son, Li Jian Yuan, painted, continuously practicing and referencing over 925 medical texts, conducting archaeological research, and recording over ten million words of notes, clarifying many difficult issues. After enduring 27 years of hard work and three revisions, he divided the work into 52 volumes, categorized into 16 sections, with each section further classified into sixty categories, using categories as the framework and herbs as the focus. The book included 1892 herbs, with 1109 illustrations and 1096 formulas, truly a monumental work. Although the book was completed, the sheer volume made it difficult for small publishers to print, and large publishing houses were unwilling to take it on due to the author’s lack of fame. Li Shizhen felt helpless and regretful about this. In the following years, he traveled extensively to find a publisher. Eventually, someone suggested inviting the influential literati Wang Shizhen to write a preface, which might lead to a breakthrough. In the 8th year of Wanli (1580), Li Shizhen approached Wang Shizhen. At that time, Li Shizhen had nothing of value except for this manuscript. Wang Shizhen recalled: “He opened his bag, revealing nothing but several dozen volumes of the ‘Compendium of Materia Medica.'” Although he sincerely requested help, Wang Shizhen refused, citing that he believed the book was not yet refined enough and hoped Li Shizhen would revise it further. After being rejected, Li Shizhen returned to Qizhou to continue editing and revising. Ten years later, Li Shizhen was over seventy, frail and suffering from illness. The content and accuracy of the book had greatly improved since the initial draft, but it had been 37 years since he began compiling it, and it still had not been published, leading to feelings of dissatisfaction and regret. In the 18th year of Wanli (1590), he entrusted his eldest son, Li Jianzhong, who was then the magistrate of Pengxi, Sichuan, to carry the manuscript back to Taicang to visit Wang Shizhen (who was then the Minister of Justice in Nanjing). This time, Wang Shizhen agreed and wrote a preface for the “Compendium of Materia Medica” on the 15th day of the first lunar month. Subsequently, with the sympathy and support of Hu Yinglong, a bibliophile and publisher in Nanjing, the “Compendium of Materia Medica” was finally printed. Upon hearing the news, Li Shizhen breathed a sigh of relief, but his health deteriorated. In 1593, the 21st year of Wanli, Li Shizhen passed away at the age of seventy-six, and he was buried with his beloved wife, Wu, on the southern bank of Yuhua Lake outside the east gate of Qizhou. The same year, the “Compendium of Materia Medica” was completed in terms of engraving but had not yet been printed or bound. In the 25th year of Wanli (1596), three years after Li Shizhen’s death, the “Compendium of Materia Medica” was officially published in Jinling.Li Shizhen never saw a complete printed and bound copy of the “Compendium of Materia Medica,” but before his death, he handwrote a testament, concluding with: “…To treat the body is to govern the world; the book should compete for brilliance with the sun and moon; to prolong the nation is to prolong the lives of the people; I shall not decay with the grass and trees…” From the book, it is recorded: “Li Shizhen, a scholar from Qizhou, was conferred the title of Wenlin Lang and served as the magistrate of Pengxi, Sichuan. Li Jianzhong, the son of Li Shizhen, and Li Jian Yuan, a student of Huangzhou, were the editors. Huang Shen, a student from the capital, and Gao Di reviewed it. Li Jianfang, a physician from the Imperial Medical Institute, and Li Jianmu, a student from Qizhou, revised it. The students, including Li Shuzong, Li Shusheng, and Li Shuxun, contributed to the volumes. The family worked together across three generations to handwrite this classic work of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Li Shizhen may have passed, but his legacy is spread across the land, and his deeds are passed down through the mouths of the people, the lean, talkative old doctor, carrying a medicine pouch and holding a medicinal hoe, traversing mountains and fields, chewing on roots, lives on among patients and the common people.

The Errors in the Transmission of the “Compendium of Materia Medica”

Gold will always shine; Hu Yinglong’s engraved “Compendium of Materia Medica” became a sensation across the country upon its release, leading to a scarcity of copies. It was subsequently reprinted and various versions emerged, with many physicians competing to collect it. Later, it was translated into Japanese, Korean, French, German, English, Russian, and other languages, spreading worldwide. The British biologist Darwin praised it as “an encyclopedia of ancient China,” and Li Shizhen’s name became renowned both domestically and internationally. From the above, we understand that the “Compendium of Materia Medica” was primarily written by Li Shizhen, with illustrations by his second son, Li Jian Yuan. Although Li Jian Yuan was a painting enthusiast and could draw better than the average person, his skills were limited, and he only attempted to depict the characteristics of the plants as accurately as possible. Many of the accompanying illustrations were still difficult to identify and lacked aesthetic appeal, leading to some errors in the herbs associated with these illustrations… As time passed to the mid-Qing Dynasty, the “Compendium of Materia Medica” had already spread widely, being both classic and popular. Many publishers, including Zhang Shaotang, rushed to print and sell it. However, without any core competitiveness, they needed to find a way to stand out; thus, the breakthrough lay in the original book’s ordinary and rough illustrations. During the Daoguang period of the Qing Dynasty, a botanist named Wu Qijun wrote two treatises on plants based on field investigations, “Investigation of Plant Names and Realities” and “Extended Investigation of Plant Names and Realities.” The former recorded 1714 medicinal substances, while the latter included 838 illustrations, especially the latter, which featured exquisite and accurate illustrations worth referencing. Compared to the original illustrations in the “Compendium of Materia Medica,” they were worlds apart. After reading this, Zhang Shaotang had a clever idea: why not replace the original illustrations of the “Compendium of Materia Medica” with Wu Qijun’s exquisite illustrations? This would compensate for the roughness of the “Compendium” illustrations, and this version would surely sell better than others. Indeed, the Zhang version of the “Compendium of Materia Medica” featured vivid and precise illustrations, clearly a high-quality edition, and thus sold exceptionally well, yielding substantial profits. However, this seemingly clever move led to the loss of many medicinal substances in later generations. Today, we will mainly discuss one such herb, Wei Ling Xian…

The Nth Transformation of True and False Wei Ling Xian

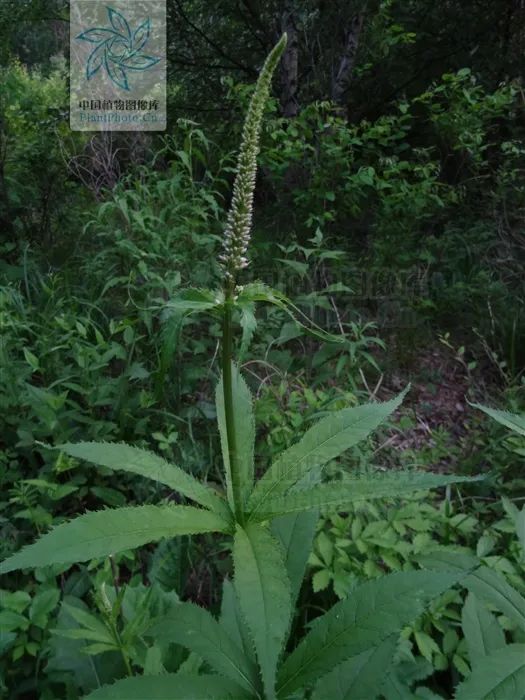

In fact, the transformation and loss of Wei Ling Xian occurred long before Li Shizhen; his account represents the second or nth error in its transformation… During the Tang Dynasty, in the Zhenyuan period, a scholar named Zhou Junchao wrote an article titled “The Tale of Wei Ling Xian,” which recorded the miraculous effects of the herb Wei Ling Xian: “In the past, there was a person in Shangzhou who suffered from a severe illness and could not walk for decades. Good doctors exhausted their skills without being able to cure him. His relatives placed him by the roadside to seek help. A monk from Silla saw him and said: ‘This illness can be cured with one herb, but I do not know if it grows in this land.’ He then entered the mountains to search and indeed found it, which was Wei Ling Xian. After taking it, he could walk within a few days. Later, a mountain man named Deng Siqi learned of this and spread the story.” This account reflects the ancient people’s emphasis on this herb and their admiration for its miraculous effects. Reviewing the materia medica texts of that time, Wei Ling Xian was described as: “Growing before other grasses, with a square stem and several opposite leaves. The flowers are light purple, and the roots are dense and become more abundant with age.” Scholars have speculated that it might be a type of plant from the Lamiaceae family,similar to the image below. It is unclear whether its efficacy led to its extinction or for other reasons, but this plant quickly disappeared after the Tang Dynasty, marking the first disappearance of “Wei Ling Xian.” (Lamiaceae)Then, from the Song to the mid-Qing Dynasty, Wei Ling Xian transformed into: “Leaves resembling willow leaves, layered, with six to seven leaves per layer like a wheel, with six to seven layers. It flowers in July, with light purple or pale white flowers, forming spikes like those of the water caltrop.” (See image below) Scholars have speculated that it might be a type of plant from the Scrophulariaceae family, which is what we now refer to as “herbaceous Wei Ling Xian.”

(Lamiaceae)Then, from the Song to the mid-Qing Dynasty, Wei Ling Xian transformed into: “Leaves resembling willow leaves, layered, with six to seven leaves per layer like a wheel, with six to seven layers. It flowers in July, with light purple or pale white flowers, forming spikes like those of the water caltrop.” (See image below) Scholars have speculated that it might be a type of plant from the Scrophulariaceae family, which is what we now refer to as “herbaceous Wei Ling Xian.” (Scrophulariaceae)Then, during the Ming Dynasty, in Li Shizhen’s time, he referenced and included some of the previous discussions about “Wei Ling Xian” and added his observations: “Its roots spread out each year, becoming more abundant with age. A single root can have hundreds of fibrous roots, with some reaching about two feet long. Initially yellow-black, it turns deep black when dried, commonly known as iron-foot Wei Ling Xian.” This description is puzzling, especially when combined with the illustrations by his son, Li Jian Yuan, which further complicate the matter.On one hand, Li Jian Yuan’s illustrations conform to the characteristics of the Scrophulariaceae Wei Ling Xian, with leaves arranged in layers like wheels, while on the other hand, they also depict the creeping form of the Ranunculaceae Wei Ling Xian. The contradictions in the book began here, with the illustrations appearing somewhat mismatched, but the overall characteristic of “leaves like wheels” became more prominent, temporarily favoring the Scrophulariaceae Wei Ling Xian.

(Scrophulariaceae)Then, during the Ming Dynasty, in Li Shizhen’s time, he referenced and included some of the previous discussions about “Wei Ling Xian” and added his observations: “Its roots spread out each year, becoming more abundant with age. A single root can have hundreds of fibrous roots, with some reaching about two feet long. Initially yellow-black, it turns deep black when dried, commonly known as iron-foot Wei Ling Xian.” This description is puzzling, especially when combined with the illustrations by his son, Li Jian Yuan, which further complicate the matter.On one hand, Li Jian Yuan’s illustrations conform to the characteristics of the Scrophulariaceae Wei Ling Xian, with leaves arranged in layers like wheels, while on the other hand, they also depict the creeping form of the Ranunculaceae Wei Ling Xian. The contradictions in the book began here, with the illustrations appearing somewhat mismatched, but the overall characteristic of “leaves like wheels” became more prominent, temporarily favoring the Scrophulariaceae Wei Ling Xian.

(Ranunculaceae)

As time passed, Zhang Shaotang’s version of the “Compendium of Materia Medica” was published, became popular, and was widely circulated. Students who purchased Zhang Shaotang’s version of the “Compendium of Materia Medica” saw the Wei Ling Xian (illustration below), which matched Li Shizhen’s description of “Wei Ling Xian” more closely. Due to the widespread popularity of this version, the mainstream understanding of “Wei Ling Xian” from the mid-Qing Dynasty to the present has been that of a Ranunculaceae plant, which, of course, has no relation to the previous descriptions of square stems, opposite leaves, and wheel-like leaves.

Not Powerful, Not Spiritual, Not Immortal: The “Wei Ling Xian”

Upon reading this, I realize the issue: the original plant of Wei Ling Xian has undergone repeated transformations, yet the efficacy attributed to Wei Ling Xian throughout history seems to remain consistent. Perhaps this is the result of many herbalists’ wishful thinking throughout the historical flow, mistaking one thing for another. In the “Compendium of Materia Medica,” Li Shizhen explains that “Wei refers to its fierce nature. Ling Xian refers to its miraculous effects.” In the records of ancient scholars, Wei Ling Xian has indeed shown significant effects in treating rheumatism and pain, as it is said: “Wei Ling Xian dispels wind, unblocks the twelve meridians, and works effectively from morning to night.” Its recorded effects on bone spurs are also quite clear. However, in contrast, the currently used Wei Ling Xian has very average clinical effects, and its efficacy in treating bone spurs is not significant, nor is its migratory nature prominent. All these issues arise from processing? From usage? From the intensive cultivation of medicinal materials? I believe a significant reason is that it is fundamentally not the miraculous Wei Ling Xian of ancient times; the miraculous Wei Ling Xian has long since disappeared into the depths of history, hidden in the vast mountains…

Concluding Remarks

The final article I have written has diverged significantly from my initial thoughts, but some points I wanted to express have been reflected. Finally, I would like to share a few insights from the process of writing and researching: 1. At the beginning of writing, I simply wanted to discuss the uncertainties of certain medicinal herbs, but during the research process, I inadvertently came across some of Li Shizhen’s discussions and records. The more I read, the more I was moved, leading to extensive quotations becoming the main body of the text, not for any other reason, but to show respect and admiration for the predecessors. It is because of them that we can conduct comparisons and verifications of many drugs today. They are the inheritors and torchbearers of Chinese culture and Traditional Chinese Medicine!2. Recently, due to some part-time work, I have interacted with some folk doctors and traditional practitioners. They have a genuine love for Traditional Chinese Medicine, which goes without saying, and they are much better than the current Westernized doctors who are unstable in their practice. However, among them, there is a group of doctors who “overly revere the ancient and despise the present,” exhibiting near superstition in their reading of ancient texts. “To believe everything in books is worse than not reading at all.” It is important to recognize that many ancient texts have their limitations and may lead to confusion and misinterpretation over the course of history… We must view ancient texts, including various versions of the “Treatise on Cold Damage” and “Essentials from the Golden Chamber,” dialectically and comparatively, and understand medicinal substances through clinical experience and analysis of ancient texts to seek effective treatments. 3. Traditional Chinese Medicine is a developing field; under the holistic view and dialectical treatment, the most important aspect is “change.” “When in difficulty, change; when changed, there is communication; when there is communication, there is longevity.” Traditional Chinese Medicine is not static. For example, the emergence of the Four Great Masters of the Jin and Yuan Dynasties may have fragmented the unity of Traditional Chinese Medicine theory, but it also led to development. We must view their academic thoughts in the context of their historical conditions, and the same applies to the integration of Chinese and Western medicine; we must look at it in the present and envision the future. 4. Whether it is a medicinal herb, a formula, or a treatment approach in Traditional Chinese Medicine, it does not arise from thin air; it is the result of countless physicians summarizing, refining, and adjusting through historical flows. The correctness of these conclusions requires us to trace back to the source, read diligently, and gain insights from the original texts to develop a profound understanding of this field. The more we understand, the more we can appreciate the spirituality of Traditional Chinese Medicine, as the saying goes: “How can one obtain such clarity? It is because there is a source of living water!” Finally, regarding some questionable medicinal materials and their changes over time, I hope that fellow practitioners of Traditional Chinese Medicine can communicate more, share knowledge, and bring back to light some herbs that have been misidentified or lost to history!

Image sources: Network, Chinese Plant Image Library