Fang Zhou Kai Qi Use Heart to Exchange Tickets

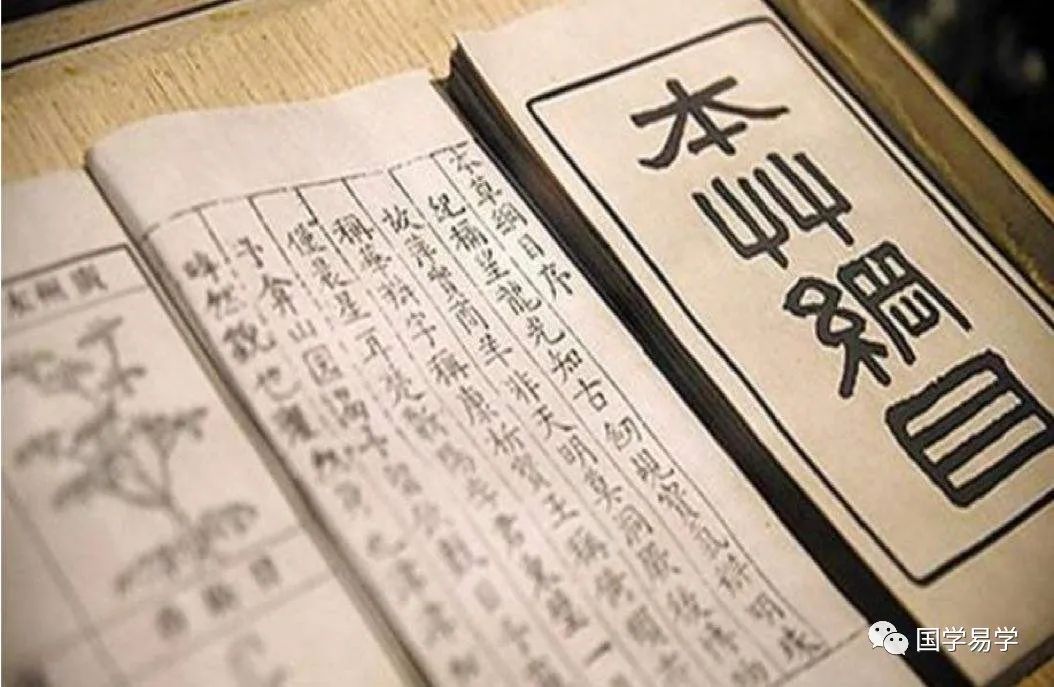

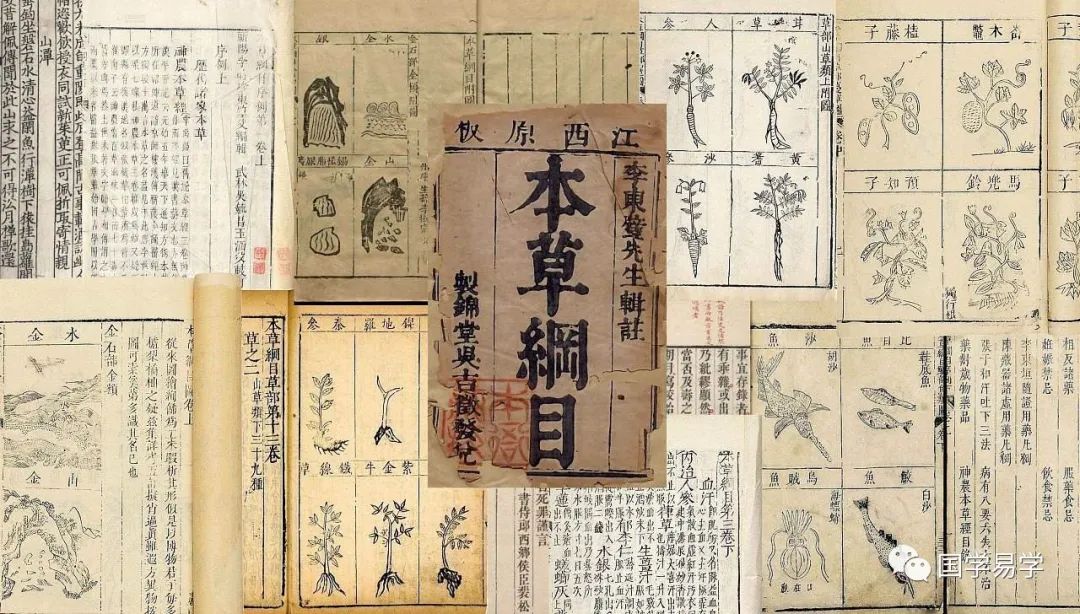

The most influential pharmacological monograph in the world is undoubtedly the “Compendium of Materia Medica” (Bencao Gangmu) written by the Ming dynasty physician Li Shizhen (1518-1593). In 2008, the State Council approved the first batch of the “National Precious Ancient Books Directory,” and Li Shizhen’s “Compendium of Materia Medica” was listed as number 01798. The book was originally published in 1593 in Nanjing by Hu Chenglong, and it is the earliest original version, consisting of 52 volumes with one volume of illustrations. It was corrected by Li Shizhen’s sons, Li Jianzhong and Li Jianyuan, and is the only version compiled by the Li family to date. In 2010, it was successfully included in the “Memory of the World Register” for the Asia-Pacific region. A revised version of the privately collected Nanjing edition of the “Compendium of Materia Medica” was also included in the third batch of the directory. The “Compendium of Materia Medica” contains approximately 1.9 million words across 52 volumes. It is divided into 16 sections based on water, fire, earth, metal and stone, grass, grains, vegetables, fruits, wood, utensils, insects, scales, shells, birds, beasts, and humans, further subdivided into a total of 60 categories, documenting 1,892 types of medicinal substances. Among these, there are 1,094 plant medicines, 443 animal medicines, 161 mineral medicines, and 194 other types of medicines (with 374 new substances added by Li Shizhen). It meticulously records and verifies the names, forms, origins, effects, and indications of these 1,892 natural medicines. It compiles 11,096 ancient prescriptions from both ancient pharmacologists and folk remedies, of which 8,100 are derived from the author’s clinical experiences or years of collection. The book is richly illustrated, with 1,109 illustrations of medicinal substances (some say 1,160 illustrations). Each medicinal substance is categorized with a standard name as the main entry, followed by an explanation as a sub-entry, borrowing the title from Zhu Xi’s “Comprehensive Mirror for Aid in Government” to name the book “Compendium of Materia Medica.” Each medicinal substance is detailed with sections on name clarification (determining the name), collection (describing the origin), differentiation of doubts, corrections (correcting past literature errors), processing (preparation methods), properties (pharmacological properties), indications (effects), inventions (Li Shizhen’s insights and research conclusions), and attached prescriptions (collecting folk remedies).

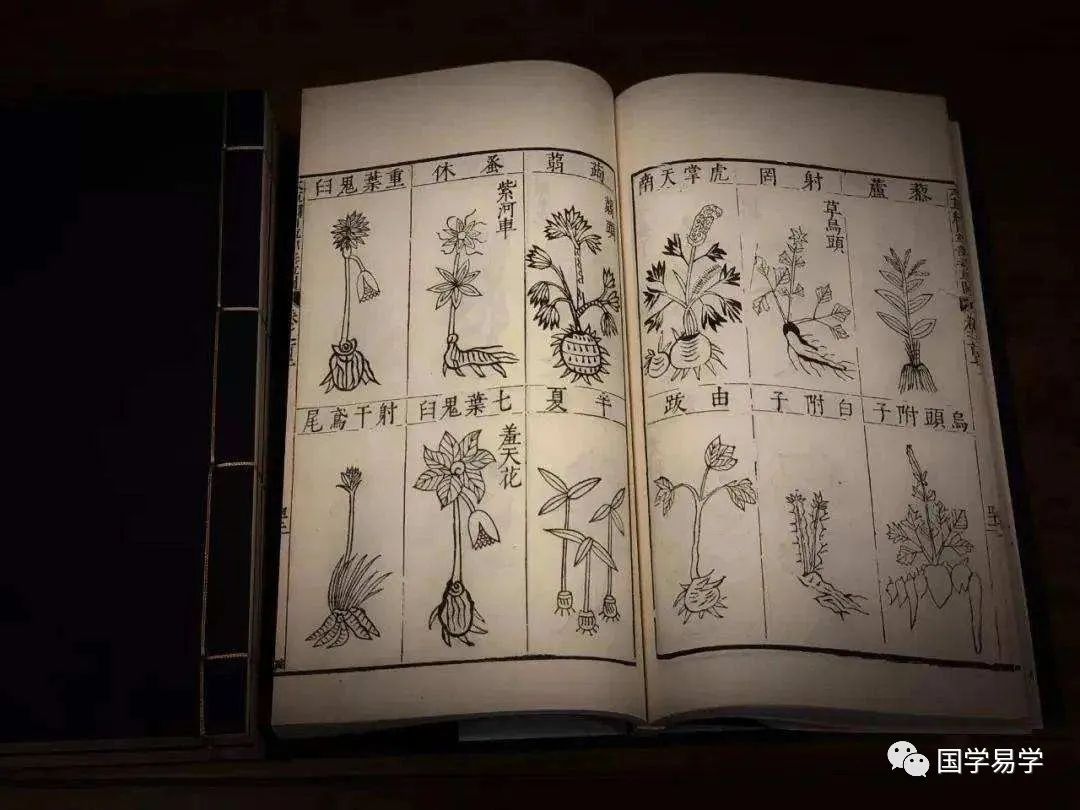

The “Compendium of Materia Medica” contains approximately 1.9 million words across 52 volumes. It is divided into 16 sections based on water, fire, earth, metal and stone, grass, grains, vegetables, fruits, wood, utensils, insects, scales, shells, birds, beasts, and humans, further subdivided into a total of 60 categories, documenting 1,892 types of medicinal substances. Among these, there are 1,094 plant medicines, 443 animal medicines, 161 mineral medicines, and 194 other types of medicines (with 374 new substances added by Li Shizhen). It meticulously records and verifies the names, forms, origins, effects, and indications of these 1,892 natural medicines. It compiles 11,096 ancient prescriptions from both ancient pharmacologists and folk remedies, of which 8,100 are derived from the author’s clinical experiences or years of collection. The book is richly illustrated, with 1,109 illustrations of medicinal substances (some say 1,160 illustrations). Each medicinal substance is categorized with a standard name as the main entry, followed by an explanation as a sub-entry, borrowing the title from Zhu Xi’s “Comprehensive Mirror for Aid in Government” to name the book “Compendium of Materia Medica.” Each medicinal substance is detailed with sections on name clarification (determining the name), collection (describing the origin), differentiation of doubts, corrections (correcting past literature errors), processing (preparation methods), properties (pharmacological properties), indications (effects), inventions (Li Shizhen’s insights and research conclusions), and attached prescriptions (collecting folk remedies). The “Compendium of Materia Medica” is divided into three parts: 1. The introductory section – “General Principles of the Compendium of Materia Medica,” which includes the table of contents and 1,160 illustrations. 2. Volumes one to four – “Preface” and “Medicinal Substances for Treating Diseases.” 3. Volumes five to fifty-two – the main content of the “Compendium of Materia Medica,” which categorizes the 1,892 recorded medicinal substances into 16 sections, further classified into 60 categories. Most medicinal substances are accompanied by 11,096 historical prescriptions, of which 8,160 are personally collected by Li Shizhen. The book represents a significant milestone in the history of Chinese pharmacology, compiling the achievements of pharmacology and medicine in China before the 16th century. The famous Ming dynasty writer Wang Shizhen praised it as “the essence of nature and reason, a comprehensive guide for understanding the world, a secret for emperors, and a treasure for the people.” The “General Catalog of the Complete Library in the Four Branches of Literature” referred to it as “the most comprehensive compendium of materia medica.” Internationally, it is regarded as a “great classic of Eastern medicine.” The renowned British biologist Darwin referred to the “Compendium of Materia Medica” as “an encyclopedia of ancient China” in his book “The Descent of Man.” The famous British historian of Chinese science and technology Joseph Needham wrote in “Science and Civilisation in China”: “In the 16th century, China had two major works on natural pharmacology: one was the ‘Essentials of Materia Medica’ from the early part of the century (1505), and the other was the ‘Compendium of Materia Medica’ from the late part of the century (1595), both of which are remarkable works.”

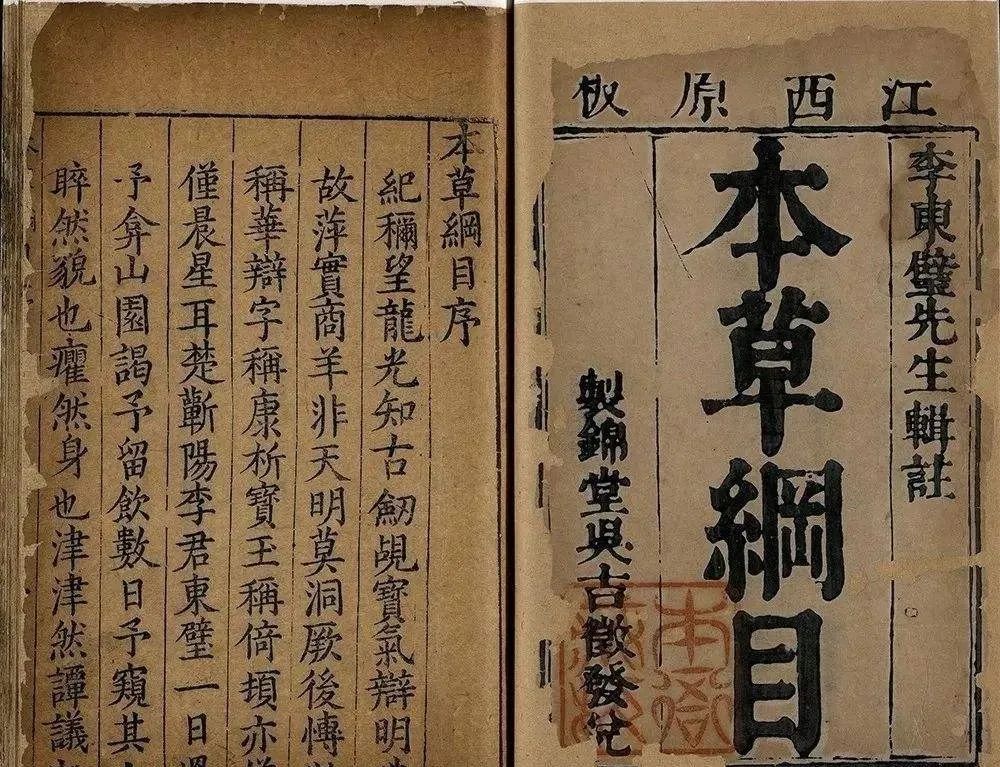

The “Compendium of Materia Medica” is divided into three parts: 1. The introductory section – “General Principles of the Compendium of Materia Medica,” which includes the table of contents and 1,160 illustrations. 2. Volumes one to four – “Preface” and “Medicinal Substances for Treating Diseases.” 3. Volumes five to fifty-two – the main content of the “Compendium of Materia Medica,” which categorizes the 1,892 recorded medicinal substances into 16 sections, further classified into 60 categories. Most medicinal substances are accompanied by 11,096 historical prescriptions, of which 8,160 are personally collected by Li Shizhen. The book represents a significant milestone in the history of Chinese pharmacology, compiling the achievements of pharmacology and medicine in China before the 16th century. The famous Ming dynasty writer Wang Shizhen praised it as “the essence of nature and reason, a comprehensive guide for understanding the world, a secret for emperors, and a treasure for the people.” The “General Catalog of the Complete Library in the Four Branches of Literature” referred to it as “the most comprehensive compendium of materia medica.” Internationally, it is regarded as a “great classic of Eastern medicine.” The renowned British biologist Darwin referred to the “Compendium of Materia Medica” as “an encyclopedia of ancient China” in his book “The Descent of Man.” The famous British historian of Chinese science and technology Joseph Needham wrote in “Science and Civilisation in China”: “In the 16th century, China had two major works on natural pharmacology: one was the ‘Essentials of Materia Medica’ from the early part of the century (1505), and the other was the ‘Compendium of Materia Medica’ from the late part of the century (1595), both of which are remarkable works.” The “Compendium of Materia Medica” was written in 1552 (the 31st year of the Jiajing reign) and completed after three revisions in 1578 (the 6th year of the Wanli reign), taking a total of 27 years. During this time, starting from 1565 (the 44th year of the Jiajing reign), Li Shizhen traveled extensively for research, covering regions such as Hubei, Jiangxi, and Zhili. It was first published in Nanjing in 1596 and quickly spread to Japan, later reaching various countries in Europe and America, being translated into more than ten languages including French, German, English, Latin, and Russian, becoming an essential reference for biologists, botanists, and medical researchers worldwide since the 16th century. 1. The earliest creation of a plant classification system.The “Compendium of Materia Medica” is based on Tang Shenwei’s “Zhenglei Bencao” and incorporates achievements from works such as “Shennong Bencao Jing,” “Mingyi Bielu,” and “Tang Bencao,” combined with Li Shizhen’s own experiences to create this monumental pharmacological work. The book provides detailed descriptions of each medicinal substance’s origin, properties, form, collection methods, processing procedures, and pharmacological studies. Particularly in the classification of medicinal substances, it employs methods of family analysis, category classification, and systematic division, ranging from inorganic to organic, and from lower to higher forms. The order is: water, fire, earth, metal and stone, grass, grains, vegetables, fruits, wood, utensils, insects, scales, shells, birds, beasts, and humans, totaling 16 sections, each further divided into several categories, totaling 62 categories. This classification method, which emphasizes the main and subcategories, was the most advanced in the world at that time. Its plant classification system predates the plant classification system proposed by the Swedish botanist Linnaeus in “Systema Naturae” (1735) by 157 years.The “Compendium of Materia Medica” records 881 types of plant medicines, with 61 additional types, totaling 942 types, plus 153 unnamed but used types, amounting to 1,095 types. It encompasses all categories of the plant kingdom: lower plants such as algae, fungi, and lichens, as well as higher plants such as mosses, ferns, gymnosperms, and angiosperms. It also includes many foreign medicinal plants, making it a comprehensive collection of plants of its time. In the book, Li Shizhen categorizes plants into five sections: grass, grains, vegetables, fruits, and the main section, totaling 30 categories, and further divides the grass section into nine categories: mountain grass, fragrant grass, wet grass, poisonous grass, creeping grass, water grass, stone grass, moss grass, and weeds. Li Shizhen’s classification method is unique in the world, even predating Linnaeus’s plant classification system by nearly 180 years. To clarify the origin and form of medicinal substances, he personally traveled to various places to collect specimens.2. Extensive references. Li Shizhen stated in the preface of the “Compendium of Materia Medica”: “Fishing through numerous books, collecting from hundreds of families.” Statistics show that Li Shizhen read nearly 800 different texts, including ancient medical books from 277 families such as “Suwen,” “Ling Shu,” “Nanjing,” “Jia Yi Jing,” and “Dongyuan Shiyang Fang.” He referenced 758 texts, including 84 major works on materia medica, and cited works from both ancient and modern times, covering over 2,000 years of pharmacological knowledge.3. Numerous editions published with the help of famous figures. The “Compendium of Materia Medica” was written in 1552 (the 31st year of the Jiajing reign) and completed after three revisions in 1578 (the 6th year of the Wanli reign), taking a total of 27 years. During this time, Li Shizhen mobilized his four sons, four grandsons, and students to participate in the writing and editing, revising it three times over a total of more than 40 years. It is said that after completing the “Compendium of Materia Medica,” Li Shizhen sought to resolve the publication issue by bringing the manuscript to Nanjing, one of the centers of the publishing industry at the time, hoping to seek publication through booksellers. However, as Li Shizhen was merely a rural doctor and the book was neither a popular novel nor a scholarly work suitable for the examination system, booksellers naturally showed little interest. This led to delays in the publication of the “Compendium of Materia Medica.” Faced with this reality, Li Shizhen pondered for a long time and decided to visit Wang Shizhen, whom he had met before, to request a preface for the book. Ten years later, in the 18th year of the Wanli reign (1590), Li Shizhen returned to Nanjing and learned that the preface had finally been completed. After three revisions of the “Compendium of Materia Medica,” it was finally published in 1590 (the 18th year of the Wanli reign) by Hu Chenglong in Nanjing, and officially released three years after Li Shizhen’s death in 1596, known as the “Nanjing Edition.” Currently, there are seven recorded copies of the Nanjing edition of the “Compendium of Materia Medica,” including three in Japan, one in the United States, one in Germany, and two in China, held by the Library of the China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences and the Shanghai Library. The copy in the Library of the China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences was previously owned by the famous Shanghai physician Ding Jiming (1912-1979) and was acquired by the library in the 1960s. The book has since been reprinted multiple times. For example, in 1603, the “Compendium of Materia Medica” was reprinted in Jiangxi by Xia Liangxin and Zhang Dingsi, known as the “Jiangxi Edition,” which is considered the second-best edition after the Nanjing edition, and many copies still exist today. In 1640, the Qianweiqi edition from Hangzhou was published, known as the Qian edition or “Hangzhou edition.” Subsequently, the number of reprints of the “Compendium of Materia Medica” gradually increased, such as the Hubei edition (1606), the Shiquge edition, and the Lida Tang edition, all printed before the end of the Ming dynasty. In 1655 (the 12th year of the Shunzhi reign), Wu Yuchang from Qiantang reprinted it. Additionally, the earliest Qing dynasty editions include the Zhang Chaolin edition (1657) and the Taihe Tang edition (1655), with many subsequent editions, the most famous being the Zhang edition and the Hefei edition published in 1885, known as the “Zhang edition” and “Hefei edition” as well as the “Weigu Zhai edition.” According to statistics, there have been many editions of the “Compendium of Materia Medica” published since its release. The “Complete Catalog of Ancient Chinese Medical Literature” records 82 versions of the “Compendium of Materia Medica” published before 1912. A total of 280 abridged editions have been published over the years.

The “Compendium of Materia Medica” was written in 1552 (the 31st year of the Jiajing reign) and completed after three revisions in 1578 (the 6th year of the Wanli reign), taking a total of 27 years. During this time, starting from 1565 (the 44th year of the Jiajing reign), Li Shizhen traveled extensively for research, covering regions such as Hubei, Jiangxi, and Zhili. It was first published in Nanjing in 1596 and quickly spread to Japan, later reaching various countries in Europe and America, being translated into more than ten languages including French, German, English, Latin, and Russian, becoming an essential reference for biologists, botanists, and medical researchers worldwide since the 16th century. 1. The earliest creation of a plant classification system.The “Compendium of Materia Medica” is based on Tang Shenwei’s “Zhenglei Bencao” and incorporates achievements from works such as “Shennong Bencao Jing,” “Mingyi Bielu,” and “Tang Bencao,” combined with Li Shizhen’s own experiences to create this monumental pharmacological work. The book provides detailed descriptions of each medicinal substance’s origin, properties, form, collection methods, processing procedures, and pharmacological studies. Particularly in the classification of medicinal substances, it employs methods of family analysis, category classification, and systematic division, ranging from inorganic to organic, and from lower to higher forms. The order is: water, fire, earth, metal and stone, grass, grains, vegetables, fruits, wood, utensils, insects, scales, shells, birds, beasts, and humans, totaling 16 sections, each further divided into several categories, totaling 62 categories. This classification method, which emphasizes the main and subcategories, was the most advanced in the world at that time. Its plant classification system predates the plant classification system proposed by the Swedish botanist Linnaeus in “Systema Naturae” (1735) by 157 years.The “Compendium of Materia Medica” records 881 types of plant medicines, with 61 additional types, totaling 942 types, plus 153 unnamed but used types, amounting to 1,095 types. It encompasses all categories of the plant kingdom: lower plants such as algae, fungi, and lichens, as well as higher plants such as mosses, ferns, gymnosperms, and angiosperms. It also includes many foreign medicinal plants, making it a comprehensive collection of plants of its time. In the book, Li Shizhen categorizes plants into five sections: grass, grains, vegetables, fruits, and the main section, totaling 30 categories, and further divides the grass section into nine categories: mountain grass, fragrant grass, wet grass, poisonous grass, creeping grass, water grass, stone grass, moss grass, and weeds. Li Shizhen’s classification method is unique in the world, even predating Linnaeus’s plant classification system by nearly 180 years. To clarify the origin and form of medicinal substances, he personally traveled to various places to collect specimens.2. Extensive references. Li Shizhen stated in the preface of the “Compendium of Materia Medica”: “Fishing through numerous books, collecting from hundreds of families.” Statistics show that Li Shizhen read nearly 800 different texts, including ancient medical books from 277 families such as “Suwen,” “Ling Shu,” “Nanjing,” “Jia Yi Jing,” and “Dongyuan Shiyang Fang.” He referenced 758 texts, including 84 major works on materia medica, and cited works from both ancient and modern times, covering over 2,000 years of pharmacological knowledge.3. Numerous editions published with the help of famous figures. The “Compendium of Materia Medica” was written in 1552 (the 31st year of the Jiajing reign) and completed after three revisions in 1578 (the 6th year of the Wanli reign), taking a total of 27 years. During this time, Li Shizhen mobilized his four sons, four grandsons, and students to participate in the writing and editing, revising it three times over a total of more than 40 years. It is said that after completing the “Compendium of Materia Medica,” Li Shizhen sought to resolve the publication issue by bringing the manuscript to Nanjing, one of the centers of the publishing industry at the time, hoping to seek publication through booksellers. However, as Li Shizhen was merely a rural doctor and the book was neither a popular novel nor a scholarly work suitable for the examination system, booksellers naturally showed little interest. This led to delays in the publication of the “Compendium of Materia Medica.” Faced with this reality, Li Shizhen pondered for a long time and decided to visit Wang Shizhen, whom he had met before, to request a preface for the book. Ten years later, in the 18th year of the Wanli reign (1590), Li Shizhen returned to Nanjing and learned that the preface had finally been completed. After three revisions of the “Compendium of Materia Medica,” it was finally published in 1590 (the 18th year of the Wanli reign) by Hu Chenglong in Nanjing, and officially released three years after Li Shizhen’s death in 1596, known as the “Nanjing Edition.” Currently, there are seven recorded copies of the Nanjing edition of the “Compendium of Materia Medica,” including three in Japan, one in the United States, one in Germany, and two in China, held by the Library of the China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences and the Shanghai Library. The copy in the Library of the China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences was previously owned by the famous Shanghai physician Ding Jiming (1912-1979) and was acquired by the library in the 1960s. The book has since been reprinted multiple times. For example, in 1603, the “Compendium of Materia Medica” was reprinted in Jiangxi by Xia Liangxin and Zhang Dingsi, known as the “Jiangxi Edition,” which is considered the second-best edition after the Nanjing edition, and many copies still exist today. In 1640, the Qianweiqi edition from Hangzhou was published, known as the Qian edition or “Hangzhou edition.” Subsequently, the number of reprints of the “Compendium of Materia Medica” gradually increased, such as the Hubei edition (1606), the Shiquge edition, and the Lida Tang edition, all printed before the end of the Ming dynasty. In 1655 (the 12th year of the Shunzhi reign), Wu Yuchang from Qiantang reprinted it. Additionally, the earliest Qing dynasty editions include the Zhang Chaolin edition (1657) and the Taihe Tang edition (1655), with many subsequent editions, the most famous being the Zhang edition and the Hefei edition published in 1885, known as the “Zhang edition” and “Hefei edition” as well as the “Weigu Zhai edition.” According to statistics, there have been many editions of the “Compendium of Materia Medica” published since its release. The “Complete Catalog of Ancient Chinese Medical Literature” records 82 versions of the “Compendium of Materia Medica” published before 1912. A total of 280 abridged editions have been published over the years. 4. “The inside is held in meetings, while the outside is fragrant.” After the first edition of the “Compendium of Materia Medica” (the Nanjing edition) was published, it did not attract much attention. In 1596, Li Jianyuan brought the “Compendium of Materia Medica” and Li Shizhen’s memorial to meet the emperor, but the Ming Emperor only commented, “The book is for review, the Ministry of Rites will know, this is an imperial decree,” and it was set aside. The “Compendium of Materia Medica” was introduced to Japan by the Japanese scholar Hayashi Dōshun in 1606 (or 1604), and in 1607, the Confucian scholar Hayashi Razan (1583-1657) purchased the “Compendium of Materia Medica” in Nagasaki and presented it to Tokugawa Ieyasu. In 1637, a reprint was published in Japan. Statistics show that between 1637 and 1714, eight editions of the “Compendium of Materia Medica” were published in Japan, and in 1783, a Japanese translation with annotations by Ono Ransan was published as “Translation of the Compendium of Materia Medica.” In 1929, the Japanese scholar Shirai Kōtarō translated it into fifteen volumes based on the Nanjing edition. Since then, various Japanese abridged and complete translations have been published, with over 30 authors researching the “Compendium of Materia Medica.”In 1647, the Polish scholar Obmige translated the “Compendium of Materia Medica” into “Flora Sinica,” published in Latin in 1657. In 1735, a French version of the “Compendium of Materia Medica” was published in Paris as part of the “Records of Chinese History, Geography, and Politics.” In England, two complete English translations of the “Compendium of Materia Medica” have circulated. According to incomplete statistics, the “Compendium of Materia Medica” has been translated into eight languages worldwide, including Latin, French, German, English, Japanese, Russian, Spanish, and Korean, and is praised as a “great classic of Eastern medicine.” Today, various editions of the “Compendium of Materia Medica” are held in the British Museum, Cambridge University Library, Oxford University Library, and the National Library of France. The Royal Library of Germany holds the Nanjing edition. Additionally, it is also collected in Russia (formerly the Soviet Union), Italy, Denmark, and other countries. The Library of Congress in the United States also holds the Nanjing edition and the Jiangxi edition.5. Five firsts in the history of medicine. According to research by Professor Yao Boyue from Peking University, Li Shizhen was the first to clearly conclude in the “Compendium of Materia Medica” that “the brain is the palace of the original spirit.” He was the first to publicly discuss gallstones in humans. He was the first to pioneer the use of ice for external application to reduce fever. He was the first to pioneer the use of steam for disinfection to prevent epidemics. He was the first to clearly propose the new TCM theory that “tonifying the spleen is not as good as tonifying the kidney, and tonifying the kidney is not as good as tonifying the Mingmen.” Furthermore, Li Shizhen clearly stated in the “Compendium of Materia Medica” that the brain is the organ of thought in humans and the central hub of mental activity, overturning the traditional view that the heart is the organ of thought.6. The embryonic form of evolution theory. The “Compendium of Materia Medica” contains ideas of evolution, as its classification of animals is arranged in an evolutionary order from lower to higher. The classification in the “Compendium of Materia Medica” starts with inorganic substances, followed by organic substances, with plants preceding animals. Among plant medicines, it lists grasses, grains, and vegetables before fruits and woods; among animal medicines, it lists insects, scales, and shells before birds and beasts, concluding with humans. Darwin referenced materials from the “Compendium of Materia Medica” in his works. Data link: Li Shizhen (1518-1593), courtesy name Dongbi, alias Binh Lake, was from Qizhou, Hubei (now Qichun County, Huanggang City, Hubei Province). In addition to the “Compendium of Materia Medica,” he also authored 11 medical works including “Binh Lake Pulse Studies” and “Examination of the Eight Extraordinary Meridians.” The initial publication of the Nanjing edition of the “Compendium of Materia Medica” was in the 21st year of the Wanli reign (1593), known as the Nanjing edition. 1. The complete edition in the Library of the China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, previously owned by the Si Bu Shan Fang collection. The complete edition in the Shanghai Library was reprinted by the Shanghai Science and Technology Publishing House in 1993. According to its collection seal, this book was previously part of the Shanghai Science and Technology Library’s collection before the liberation. 2. The complete edition in the National Archives of Japan’s Cabinet Library, presented by Naoki Ikeguchi. This edition is known for the annotations made by Kurukura Genpaku in the 19th year of Keichō (1614), making it known to later generations. Genpaku supplemented his father’s work “Nōdoku” based on the “Compendium of Materia Medica,” which was completed in the 13th year of Keichō (1608). The Cabinet Library’s copy of this Nanjing edition was reprinted in 1992 by Osaka’s Orient Publishing. The complete edition in the National Diet Library was previously owned by Tazawa Zhongshu and has been stored in various places, later donated to the National Diet Library by Yoshikazu Hara. Although the Toyo Bunko edition is a complete edition, part of it is a handwritten supplement, previously owned by Iwasaki Kyūya. Iwasaki Kyūya purchased it from George Ernest Morrison’s old Morrison Library and stored it in this library, which later became known as the Toyo Bunko. The complete edition in the library of Tohoku University was previously owned by Kanō Tōkichi. The complete edition in the Kyoto Prefectural Botanical Garden is missing volumes 19-21 and 47-49, previously owned by the botanist Shirai Kōtarō. It was once part of the collection of Kishu’s Kobara Momodō. The complete edition in the Takeda Science Foundation’s Kyōu Shūkan is now only preserved in volumes 19-28, totaling 10 volumes. The complete edition in the Miyagi Prefectural Library is missing volumes 36-38, previously owned by various scholars and passed down to the present. 3. The complete edition in the British National Library is an old collection from Japan. The “Compendium of Materia Medica” is a pharmacopoeia published with the help of famous figures. Li Shizhen: A talented individual in both poetry and painting.

4. “The inside is held in meetings, while the outside is fragrant.” After the first edition of the “Compendium of Materia Medica” (the Nanjing edition) was published, it did not attract much attention. In 1596, Li Jianyuan brought the “Compendium of Materia Medica” and Li Shizhen’s memorial to meet the emperor, but the Ming Emperor only commented, “The book is for review, the Ministry of Rites will know, this is an imperial decree,” and it was set aside. The “Compendium of Materia Medica” was introduced to Japan by the Japanese scholar Hayashi Dōshun in 1606 (or 1604), and in 1607, the Confucian scholar Hayashi Razan (1583-1657) purchased the “Compendium of Materia Medica” in Nagasaki and presented it to Tokugawa Ieyasu. In 1637, a reprint was published in Japan. Statistics show that between 1637 and 1714, eight editions of the “Compendium of Materia Medica” were published in Japan, and in 1783, a Japanese translation with annotations by Ono Ransan was published as “Translation of the Compendium of Materia Medica.” In 1929, the Japanese scholar Shirai Kōtarō translated it into fifteen volumes based on the Nanjing edition. Since then, various Japanese abridged and complete translations have been published, with over 30 authors researching the “Compendium of Materia Medica.”In 1647, the Polish scholar Obmige translated the “Compendium of Materia Medica” into “Flora Sinica,” published in Latin in 1657. In 1735, a French version of the “Compendium of Materia Medica” was published in Paris as part of the “Records of Chinese History, Geography, and Politics.” In England, two complete English translations of the “Compendium of Materia Medica” have circulated. According to incomplete statistics, the “Compendium of Materia Medica” has been translated into eight languages worldwide, including Latin, French, German, English, Japanese, Russian, Spanish, and Korean, and is praised as a “great classic of Eastern medicine.” Today, various editions of the “Compendium of Materia Medica” are held in the British Museum, Cambridge University Library, Oxford University Library, and the National Library of France. The Royal Library of Germany holds the Nanjing edition. Additionally, it is also collected in Russia (formerly the Soviet Union), Italy, Denmark, and other countries. The Library of Congress in the United States also holds the Nanjing edition and the Jiangxi edition.5. Five firsts in the history of medicine. According to research by Professor Yao Boyue from Peking University, Li Shizhen was the first to clearly conclude in the “Compendium of Materia Medica” that “the brain is the palace of the original spirit.” He was the first to publicly discuss gallstones in humans. He was the first to pioneer the use of ice for external application to reduce fever. He was the first to pioneer the use of steam for disinfection to prevent epidemics. He was the first to clearly propose the new TCM theory that “tonifying the spleen is not as good as tonifying the kidney, and tonifying the kidney is not as good as tonifying the Mingmen.” Furthermore, Li Shizhen clearly stated in the “Compendium of Materia Medica” that the brain is the organ of thought in humans and the central hub of mental activity, overturning the traditional view that the heart is the organ of thought.6. The embryonic form of evolution theory. The “Compendium of Materia Medica” contains ideas of evolution, as its classification of animals is arranged in an evolutionary order from lower to higher. The classification in the “Compendium of Materia Medica” starts with inorganic substances, followed by organic substances, with plants preceding animals. Among plant medicines, it lists grasses, grains, and vegetables before fruits and woods; among animal medicines, it lists insects, scales, and shells before birds and beasts, concluding with humans. Darwin referenced materials from the “Compendium of Materia Medica” in his works. Data link: Li Shizhen (1518-1593), courtesy name Dongbi, alias Binh Lake, was from Qizhou, Hubei (now Qichun County, Huanggang City, Hubei Province). In addition to the “Compendium of Materia Medica,” he also authored 11 medical works including “Binh Lake Pulse Studies” and “Examination of the Eight Extraordinary Meridians.” The initial publication of the Nanjing edition of the “Compendium of Materia Medica” was in the 21st year of the Wanli reign (1593), known as the Nanjing edition. 1. The complete edition in the Library of the China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, previously owned by the Si Bu Shan Fang collection. The complete edition in the Shanghai Library was reprinted by the Shanghai Science and Technology Publishing House in 1993. According to its collection seal, this book was previously part of the Shanghai Science and Technology Library’s collection before the liberation. 2. The complete edition in the National Archives of Japan’s Cabinet Library, presented by Naoki Ikeguchi. This edition is known for the annotations made by Kurukura Genpaku in the 19th year of Keichō (1614), making it known to later generations. Genpaku supplemented his father’s work “Nōdoku” based on the “Compendium of Materia Medica,” which was completed in the 13th year of Keichō (1608). The Cabinet Library’s copy of this Nanjing edition was reprinted in 1992 by Osaka’s Orient Publishing. The complete edition in the National Diet Library was previously owned by Tazawa Zhongshu and has been stored in various places, later donated to the National Diet Library by Yoshikazu Hara. Although the Toyo Bunko edition is a complete edition, part of it is a handwritten supplement, previously owned by Iwasaki Kyūya. Iwasaki Kyūya purchased it from George Ernest Morrison’s old Morrison Library and stored it in this library, which later became known as the Toyo Bunko. The complete edition in the library of Tohoku University was previously owned by Kanō Tōkichi. The complete edition in the Kyoto Prefectural Botanical Garden is missing volumes 19-21 and 47-49, previously owned by the botanist Shirai Kōtarō. It was once part of the collection of Kishu’s Kobara Momodō. The complete edition in the Takeda Science Foundation’s Kyōu Shūkan is now only preserved in volumes 19-28, totaling 10 volumes. The complete edition in the Miyagi Prefectural Library is missing volumes 36-38, previously owned by various scholars and passed down to the present. 3. The complete edition in the British National Library is an old collection from Japan. The “Compendium of Materia Medica” is a pharmacopoeia published with the help of famous figures. Li Shizhen: A talented individual in both poetry and painting.