The great pharmacologist of the Ming Dynasty, Li Shizhen, after “thirty years of experience and studying over eight hundred families, with three revisions of the manuscript,” finally compiled the unprecedented and practically needed monumental work of materia medica, the Ben Cao Gang Mu (Compendium of Materia Medica). However, the publication and printing of this work were forced to stagnate due to his personal lack of influence. In this situation, he had to continue his long travels and investigations throughout Jiangnan to further supplement and perfect the book. During this period, he discovered various important medicinal materials such as the “pufferfish poisoning” and the “identification of the authenticity of the Qishi snake,” and he also saw precious medicinal materials like “Shanqi” (mountain lacquer) and “Hui Xiang” (fennel) brought into the country by remote ethnic minorities and overseas merchants in Nanjing. He investigated rare medicinal materials such as Shan Nai (Zingiber zerumbet), Man Tuo Luo (Mandragora), Lu Gan Shi (Calamine), and Fan Mu Bie (Bitter cucumber) brought back by Zheng He from abroad, greatly enriching and perfecting the book. At the same time, he tirelessly sought to publish and circulate the work, personally visiting Wang Shizhen in Taicang to request a preface to expand its influence, and finally fulfilled his long-cherished wish in his later years. After the book was published, it quickly spread across the country, attracting attention from all levels of society, and through various channels, it rapidly reached countries around the world, profoundly impacting the study of natural history, biology, botany, and other disciplines.

In 1578 (the sixth year of the Wanli era of the Ming Dynasty), after enduring hardships and undergoing three major revisions, Li Shizhen finally completed his great Eastern medical classic, the Ben Cao Gang Mu. To ensure that this medical classic could serve the purpose of benefiting the people, he aimed to disseminate this practical medical knowledge to the masses as quickly as possible, rather than letting it be “shelved and passed on to future generations” after its completion. Therefore, the issue of publication became urgent for Li, who was over sixty years old. As he was merely a physician relying on his practice for a living, he could not publish this monumental work relying solely on his personal efforts in Qizhou, Huangzhou, and Wuchang, so he decided to seek a solution in Nanjing. Despite his advanced age and declining health, in 1580 (the eighth year of the Wanli era), he set out with his disciple, Pang Xian, from his hometown in Yuhu, traveling downstream to Jinling.

Jinling, now Nanjing, was once the capital in the early Ming Dynasty and was a place where literati gathered and people from various regions coexisted. After the establishment of the feudal dynasty by the Ming rulers, they adopted a policy of “self-reliance” to encourage the development of production, and the rapid development of agriculture promoted changes in the social economy, leading to a prosperous situation in commerce and industry. The paper and printing industries had greatly developed during the Ming Dynasty, with movable type printing widely used and popularized. Many wealthy booksellers used copper movable type to publish various books, making Jinling the center of the publishing industry in the country and a gathering place for booksellers. Therefore, Li’s choice to publish the Ben Cao Gang Mu in Jinling had profound historical roots and social background. However, at that time, most booksellers were keen on printing works related to “Cheng-Zhu Neo-Confucianism” and other feudal moral guidelines, ignoring Li’s immortal classic meant to benefit the people, and generally lacking a correct understanding of it. Thus, despite Li’s many years of travel in Jinling, he was unable to find a suitable publishing house to cooperate with, causing the publication of the Ben Cao Gang Mu to be forced to stagnate. His investigations and life in Jiangnan led to significant changes in Li Shizhen’s thoughts and provided him with new insights. Although the book had not yet been printed, he remained undeterred and instead became more determined, using this opportunity to further supplement and perfect the Ben Cao Gang Mu by “exploring remote and dangerous places for their products.” He personally witnessed a person die from pufferfish poisoning in Jiangyin, thus recording in Volume 44: Pufferfish: “I personally witnessed a Confucian scholar in Jiangyin die after consuming this; pufferfish must not be eaten. It swelled overnight to the size of a water chestnut…” In order to distinguish the authenticity of the Qishi snake, he not only climbed Longfeng Mountain north of Qizhou multiple times but also traveled to Xingguo Prefecture in Jiangnan for investigation, writing the well-known Qishi Snake Biography, vividly depicting the morphological characteristics of the Qishi snake and pointing out the key points for identification: “When snakes die, they all close their eyes, but the Qizhou flower snake’s eyes remain open.” (In Volume 43: White Flower Snake) If it were not for his field investigations, how could he have such profound insights? In Jinling, he not only saw many newly popular precious medicinal materials, such as “Shanqi,” but also had the opportunity to interact extensively with merchants from Quanzhou, gaining in-depth understanding and investigation of a batch of overseas medicinal materials and those from remote ethnic minorities. For example, “Shanqi” was first recorded in the Ben Cao Gang Mu under the section on herbs, stating: “This medicine has recently emerged, used as a key medicine for gold wounds in the southern army, said to have miraculous effects…” In Volume 26: Fennel, Li recorded: “Those brought from abroad are indeed as large as cedar nuts… commonly known as foreign fennel… its shape and color are quite different from Chinese fennel, but the taste is the same. Northerners use it to chew and relieve intoxication.” From the above records of medicinal materials, it can be seen that during his investigations in Jinling, Li had close interactions with traders from various ethnic minorities and overseas merchants. Medicinal materials such as Shan Nai (Zingiber zerumbet), Man Tuo Luo (Mandragora), Yue Ji Hua (Rose), A Fu Rong (Cotton rose), Lu Gan Shi (Calamine), and Fan Mu Bie (Bitter cucumber) were all newly added varieties during this period, greatly enriching the treasure trove of Chinese pharmacology. During the Yongle era of the Ming Dynasty, Zheng He made seven voyages to the Western seas, visiting over thirty countries and regions, leading to unprecedented international exchanges. Some precious medicinal materials brought back and cultivated by Zheng He (according to Mai Huan’s Ying Ya Sheng Lan) provided valuable foundational identification materials for Li’s research work. The chapters in the Ben Cao Gang Mu that introduce foreign medicinal materials are rich and substantial, closely related to his investigative activities in Jinling. Although the Ben Cao Gang Mu was completed at this time, he continued to devote all his energy to supplementing and revising the book’s content in the following years, tirelessly writing until his last breath, truly embodying the spirit of perseverance.

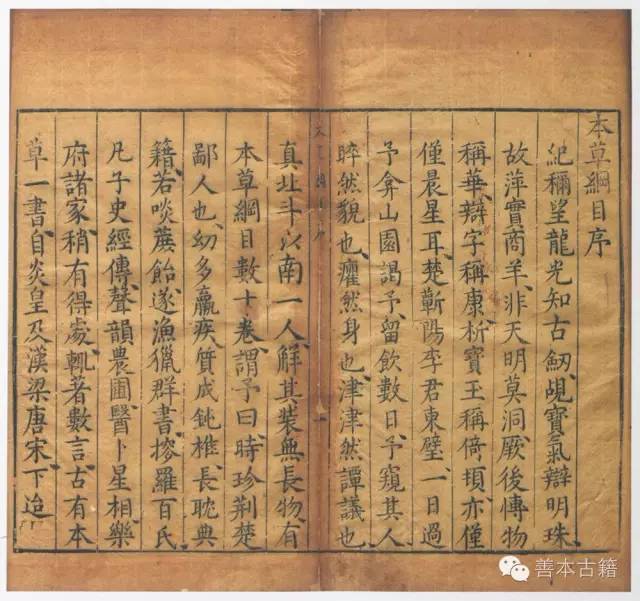

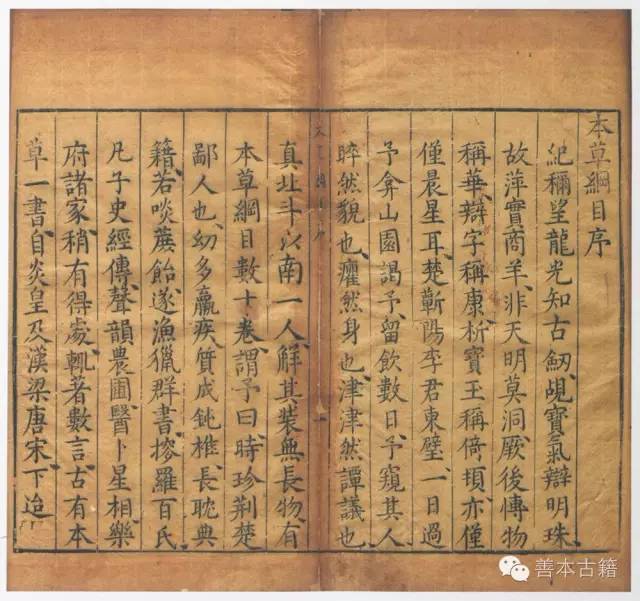

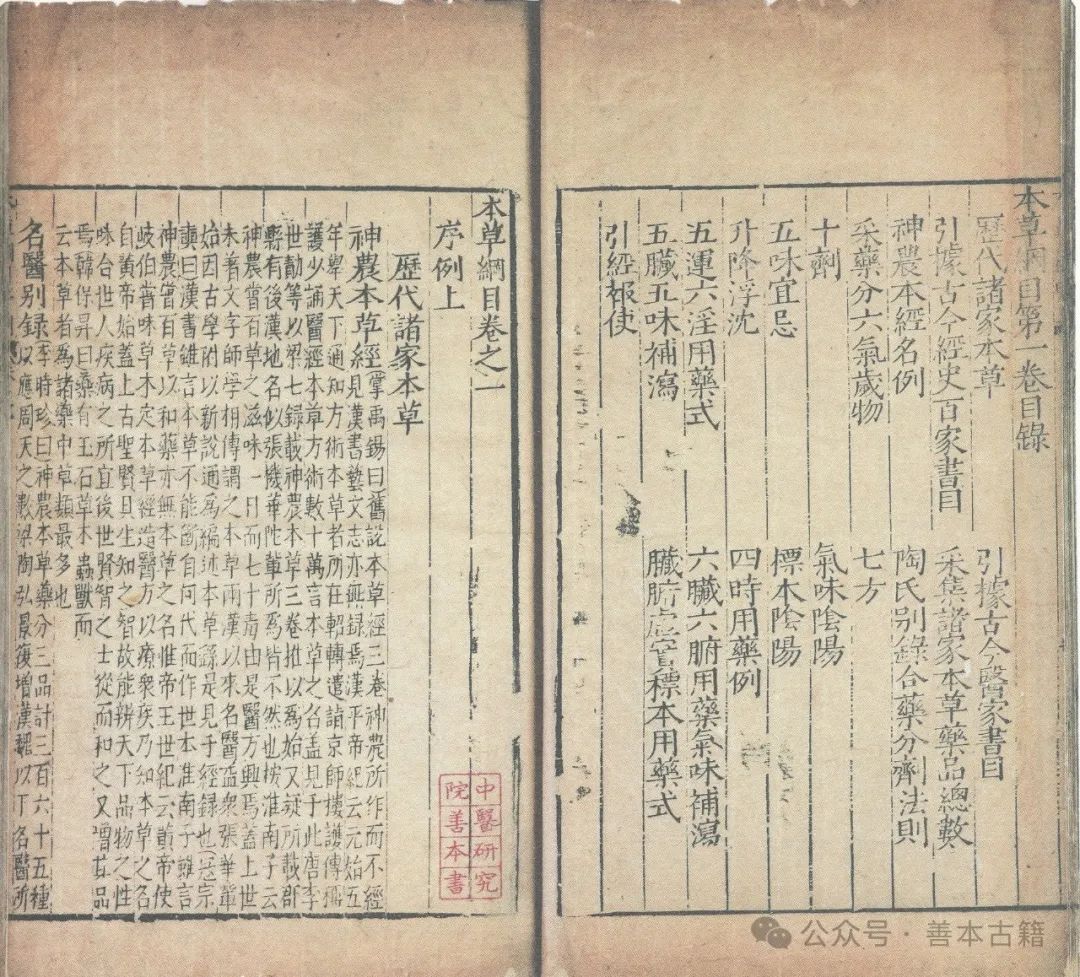

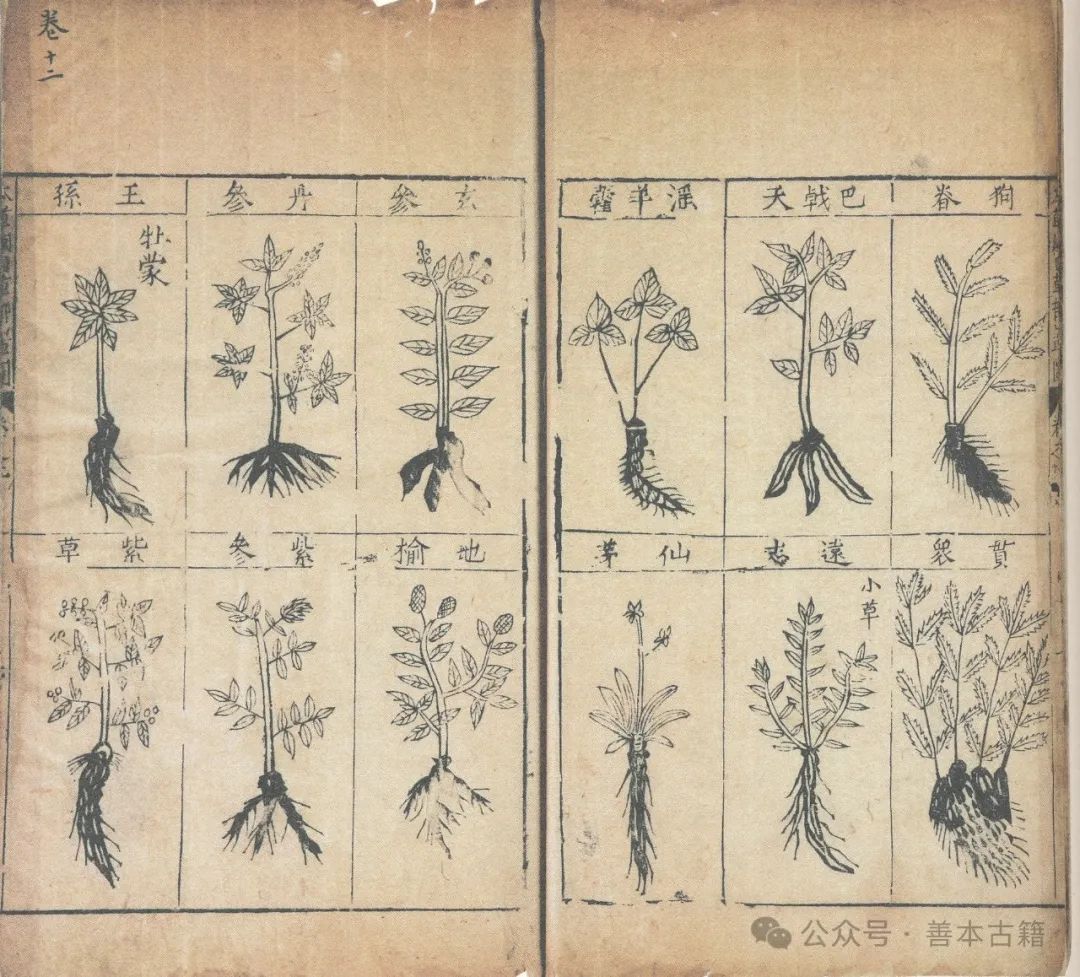

While Li was tirelessly working to complete the Ben Cao Gang Mu, he also continuously sought to publish and circulate the work. On September 9, 1580 (the eighth year of the Wanli era), he specially visited the famous Ming Dynasty literary figure Wang Shizhen at the Kan Mountain Garden in Taicang, Jiangsu. At that time, Wang was at home after being dismissed from his official position, and the two met with great joy, engaging in deep discussions for several days. Li’s unique and profound insights, along with his indomitable spirit, greatly impressed this literary connoisseur, who praised Li Shizhen as “the only person south of the Big Dipper.” After reading the Ben Cao Gang Mu in detail, he was even more amazed and gladly wrote a preface for it. In the preface, he evaluated: “This is not merely a medical book; it is indeed a profound treatise on nature, a comprehensive record of plants, and a treasure for both emperors and subjects.” Historical verification shows that this outstanding preface accurately reflects the evaluation of the book and adds a significant touch to the publication of the Jinling edition of the Ben Cao Gang Mu. With sincere effort, Li finally, after many twists and turns, contacted the Jinling bookseller Hu Chenglong in the eighteenth year of Wanli (1590). After reading the manuscript of the Ben Cao Gang Mu, Hu deemed it a highly collectible masterpiece and decided to fund its printing. In 1590 (the eighteenth year of Wanli), by this time, Li was already in his seventies, and due to accumulated labor and illness, he returned to his hometown in Qizhou, entrusting the printing matters to his eldest son, Jianzhong. Although Li had been bedridden for a long time, he still guided the editing work from his sickbed, providing revision suggestions. The high quality of the Jinling edition of the Ben Cao Gang Mu reflects Li’s rigorous academic spirit. In Volume 1, the “Formulas for the Treatment of Organ Deficiencies” are prominently marked with the titles “Excessive and Deficient Treatments,” “Heat and Cold Treatments,” and “Symptoms of Heat and Cold” in bold ink, reflecting Li’s strict requirements for publication standards. In the twenty-first year of Wanli (1593), the book was officially published in Nanjing, and three years later (1596), it was officially released, quickly becoming a must-have book for all social classes. Since the Ming and Qing Dynasties and even to the present day, it has had a profound influence and is highly regarded. After the publication of the Jinling edition of the Ben Cao Gang Mu, the study of materia medica flourished during the Ming and Qing Dynasties. This period focused on organizing and summarizing the achievements in pharmacological mechanisms and clinical applications since the Jin and Yuan Dynasties, resulting in a number of works that used the Ben Cao Gang Mu as the main reference, selecting medicinal materials that were precise and practical. Most of these works combined medicinal materials, illustrations, and formulas, forming the characteristics of materia medica studies during this period. The most representative works reflecting the new developments of the time are Zhao Xueming’s Ben Cao Gang Mu Shi Yi and Wu Qijun’s Plant Names and Realities. These two works supplemented the medicinal materials not included in the Ben Cao Gang Mu and expanded its content. Influenced by the Ben Cao Gang Mu, later materia medica scholars drew from the new achievements in pharmacological research from the Jin and Yuan periods, explaining the functions of medicinal materials from the perspectives of flavor, yin and yang, and organ meridians, shifting from ancient textual interpretations to practical clinical research. The emergence of the Jinling edition of the Ben Cao Gang Mu and the subsequent flourishing of materia medica research marked a leap in the discipline of materia medica in terms of content, form, quantity, and quality, leading to increasing maturity. It not only guided medical practice at the time but also continues to guide medical practice today, with the medicines and formulas it contains still widely used in the medical community. Many of these formulas and medicines have been validated by modern science. Inspired by the Ben Cao Gang Mu, the variety of research on Chinese herbal medicine is increasing, the research fields are expanding, and new areas such as pharmacognosy, pharmacology, and pharmaceutical chemistry are being explored. Modern researchers of traditional Chinese medicine often regard the Ben Cao Gang Mu as essential reference literature, with many new drugs and sources being discovered from this work. According to relevant data, approximately 60% of the plant medicines in this work have undergone modern research. The publication of the Ben Cao Gang Mu has sparked great interest among later botanists, biologists, zoologists, mineralogists, chemists, as well as philosophers, historians, thinkers, and writers, all eager to explore and discover. Why does the Ben Cao Gang Mu possess such vitality and profound influence? The key lies in its profound revelation of the laws and essence of “materia medica” and other fields of nature, correctly predicting its future, and being continuously validated by practical applications. Therefore, it is hailed as “the ancient Chinese encyclopedia.” The Jinling edition closely aligns with Li’s original work and is the earliest and most precious version of the Ben Cao Gang Mu. According to verified information, there are currently seven existing versions, of which five are held abroad, and only two are in China, located in the library of the China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences in Beijing and the Shanghai Science and Technology Publishing House. The historical and scientific academic value of the Jinling edition of the Ben Cao Gang Mu is immeasurable. Countries around the world regard it as a “classic” and proudly house it in their important national libraries, especially the Royal Library in Berlin, Germany, and the Library of Congress in the United States, which holds the “Jinling edition” revised by Japanese scholar Mori Ritsu, making it even more precious. This is a pride of traditional Chinese medicine and of the Chinese nation. Shortly after the publication of the Ben Cao Gang Mu, with the commercial trade and the arrival of scholars or missionaries to China, it spread to Japan, Korea, and various Western European countries, and was subsequently translated into multiple languages including Korean, Japanese, English, French, German, Russian, and Latin. Its eastward and westward dissemination has had a profound impact on the development of pharmacology worldwide. The reason it has been pursued by foreign luminaries for centuries is primarily due to the inexhaustible essence and wisdom it contains, revealing the scientific laws and essence of the natural world, and it will shine brightly in the history of world science.

References [1] Chen Cunren. Chronology of Li Shizhen. Journal of Chinese Medical History. 1982, 12(2): 77. [2] Compiled by the Historical Office of the People’s Education Press. Chinese History (Volume 2) (Junior High School Textbook). Beijing: People’s Education Press, 1998: 189. [3] Zhang Huijian. Li Shizhen. Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Publishing House, 1954: 43. [4] Ming Li Shizhen. Annotated Edition of the Ben Cao Gang Mu. Beijing: People’s Health Publishing House, 1977: Volume 4: 2465, 2401, Volume 2: 767, Volume 3: 1623. [5] Compiled by the Medical History Literature Room of Hubei Province Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Research on Li Shizhen. Guangzhou: Guangdong Science and Technology Publishing House, 1984: 8, 21. [6] Wu Zuoxin. Chronology of Li Shizhen. In: Compiled by the History of Pharmacy Society of the Chinese Pharmaceutical Association. Collection of Papers on Li Shizhen Research. Wuhan: Hubei Science and Technology Publishing House, 1983: 32. [7] Wang Shizhen. Original Preface to the Ben Cao Gang Mu. In: Duan Yishan. Ancient Medical Literature (Textbook for Higher Medical Colleges). Shanghai: Shanghai Science and Technology Publishing House, 1989: 148. [8] Ma Jixing. Investigation of the Versions of the Ben Cao Gang Mu. In: Compiled by the History of Pharmacy Society of the Chinese Pharmaceutical Association. Collection of Papers on Li Shizhen Research. Wuhan: Hubei Science and Technology Publishing House, 1983: 115. [9] Edited by Beijing University of Chinese Medicine. History of Chinese Medicine (Textbook for Higher Medical Colleges). Shanghai: Shanghai Science and Technology Publishing House, 1978: 45.

If you wish to participate in discussions related to ancient texts, please reply to the 【Shan Ben Gu Ji】 public account message: Group Chat

Welcome to join the Shan Ben Gu Ji learning and exchange community.