The Huangdi Neijing (Yellow Emperor’s Inner Canon) is regarded as a classic of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM). The more one reads it, the deeper one understands its profound insights. We are grateful to our ancestors for leaving us such a precious cultural heritage.

The Huangdi Neijing states: “Do not treat the already sick, but prevent the sick from becoming ill; do not treat the already chaotic, but prevent chaos from arising.” This means that a superior physician does not treat diseases that have already manifested but instead ensures that one does not fall ill in the first place.

The Huangdi Neijing is a spiritual and cultural legacy left to us by our ancestors, a unique and invaluable treasure that has been passed down through generations. It is a book that enhances wisdom and is worth reading repeatedly with care.

However, many people are unaware of this wealth passed down from our ancestors. Many believe that discussions about health are only for the elderly, and health preservation is even more so. Many young people do not know how to cherish their bodies or understand what a healthy lifestyle is. Many live irregularly, eat excessively, and lead chaotic lives, indulging in overeating and exhausting their health.

The Huangdi Neijing teaches us that health is in our own hands; health leads to longevity, but longevity does not equate to health. Only with health and happiness can one have a fulfilling life. Your daily habits determine whether you can have a healthy body. Each of us, regardless of age, should pay attention to our lives and health, and start practicing health preservation now. This is the only way to have a healthy body and a beautiful life, making life rich and meaningful. Health and happiness are the true essence of life.

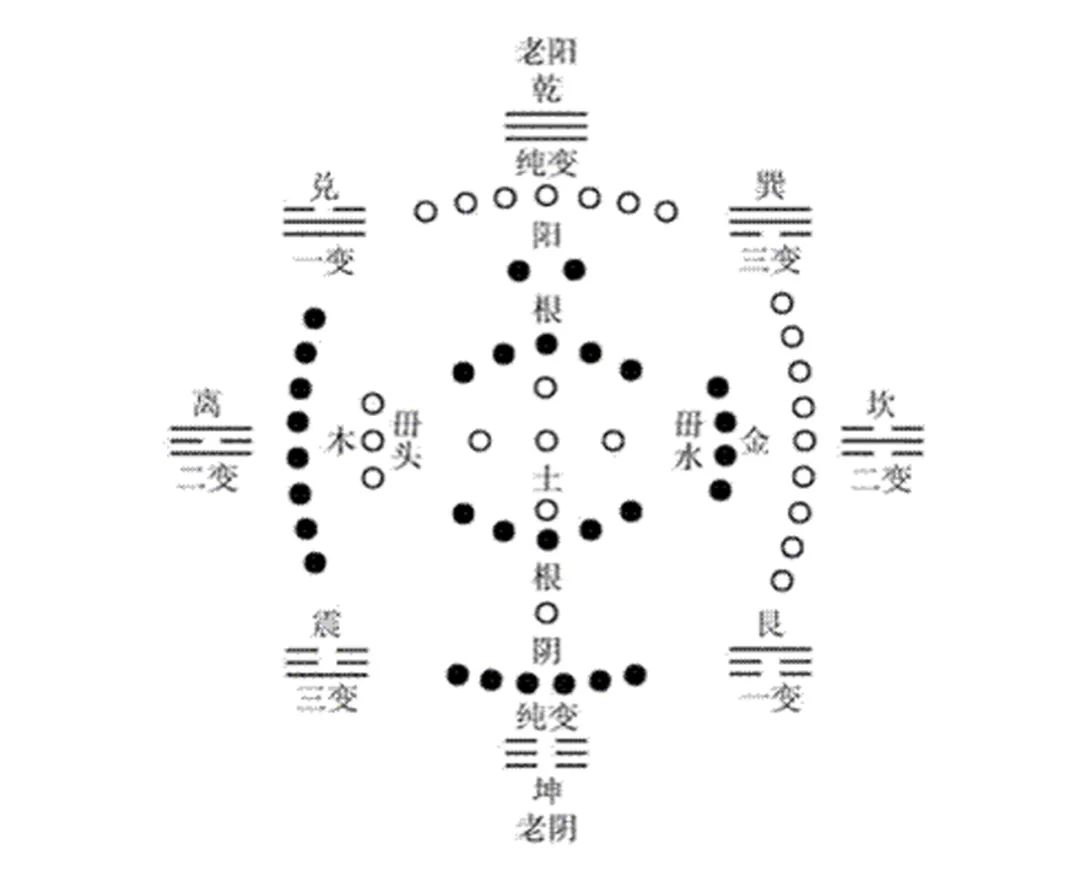

The Huangdi Neijing, particularly the Suwen (Plain Questions), is indeed a classic. It begins by addressing the issue that “people today, at fifty years of age, show signs of decline in their physical abilities,” and proposes principles and methods for health preservation: “Follow the principles of yin and yang, harmonize with numerical methods, eat and drink in moderation, maintain regularity in daily activities, and avoid unnecessary labor.” This is a direct and insightful statement. However, its greatest achievement lies in finding the connection between life and nature, using the ever-changing concepts of yin and yang to reflect its laws. The ancient sages’ discussions on yin and yang are both admirable and worthy of respect.

I believe the greatness of the Huangdi Neijing does not lie solely in its theories but in the long-term observations and explorations that preceded these theories. For example, “Men do not exceed eighty, and women do not exceed seventy,” refers to the relationship between life rhythms and reproduction. When a man reaches sixty-four years of age, “teeth and hair fall away,” because teeth are the flowers of the kidneys, governed by kidney qi. “Teeth and hair fall away” indicates that the body’s ability to gather and generate has diminished, leading to the loss of teeth and hair. When men and women reach these stages, their bodies begin to decline, and their resistance, organ function, and energy all weaken. Women, after the age of forty-nine, begin to experience menopause and lose their reproductive capacity. The correspondence between seasonal climates and the five internal organs also reflects the solid observational foundation of the Huangdi Neijing. This spirit of problem discovery, contradiction observation, and law-seeking is what every physician should inherit.

The reason the Huangdi Neijing is a must-read in TCM, and even in all medicine, is not that it summarizes all methods for disease prevention and treatment, but because it provides foundational discussions on the five internal organs and meridians. As the saying goes, “If the name is not correct, the words will not be smooth; if the words are not smooth, the treatment will not be effective.” To discuss treatment, one must differentiate patterns; to differentiate patterns, one must examine symptoms and seek causes. Only with causes can there be effects, and it is the Huangdi Neijing that provides the causes, leading to the fruit of Chinese medicine. Moreover, the treatment philosophy of “Do not treat the already sick, but prevent the sick from becoming ill; do not treat the already chaotic, but prevent chaos from arising” predates Western preventive concepts by many years.

In chapters such as Suwen: On the Distinction of the Five Internal Organs, the basic characteristics of the five internal organs are recorded. In chapters like Suwen: On the Three Parts and Nine Pulses and Suwen: On the True Organs of the Jade Machine, the locations and methods of pulse diagnosis, as well as the seasonal variations of pulse patterns, are discussed. I was pleasantly surprised to find the original text on acupuncture and moxibustion techniques in Suwen: On the Complete Form of Life, stating, “In all acupuncture, one must first treat the spirit.” These familiar phrases made me feel even closer to the Huangdi Neijing. Additionally, in Suwen: On the Eight Correct Spirits, it states, “Once the five internal organs are established and the nine pulses are prepared, only then can one retain the needle,” proposing the theory of “when evil qi is abundant, it is real; when vital qi is depleted, it is deficient,” centered on the balance of evil and righteous qi.

When discussing the characteristics of the Huangdi Neijing, the first word that comes to mind is “change.” For example, why does the lung cause coughing? The answer is that all five internal organs can cause coughing, not just the lungs. From this, I realize that even a single symptom is infinitely variable, let alone treatment methods. The thoughts in the Huangdi Neijing are vast. In Suwen: On the Different Methods and Appropriate Formulas, it states that each disease requires different treatments, depending on the geographical conditions.

The Huangdi Neijing is also known as the Ling Shu (Miraculous Pivot), which primarily discusses the theories of acupuncture meridians and acupoints. Throughout my studies in meridian and acupoint theory, I have memorized much of its content, which has given me a new understanding of the human body, moving beyond mere anatomical perspectives. It has deepened my understanding of the connections between the internal organs and inspired many new ideas. For instance, the phrase from the hand Taiyin lung meridian, “returning to the stomach’s opening,” suggests the feasibility of treating lung diseases while also addressing stomach regulation to enhance therapeutic effects. I am merely a beginner, yet I can gain insights; for the sages, it is undoubtedly even more profound: the treatment of cold damage by Zhang Zhongjing, the cooling methods of the Four Great Masters of the Jin and Yuan Dynasties, and the warm disease theories of the Ming and Qing Dynasties have all drawn from the Huangdi Neijing to varying degrees.

The more I study, the more I feel the profundity of TCM, and the more I read the Huangdi Neijing, the more I admire the greatness of our ancestors. I have also learned more TCM theoretical knowledge from the Huangdi Neijing, laying a solid foundation for my future studies in TCM. (Author: Resident Physician, First Affiliated Hospital of Henan University of Chinese Medicine, Class of 2018)