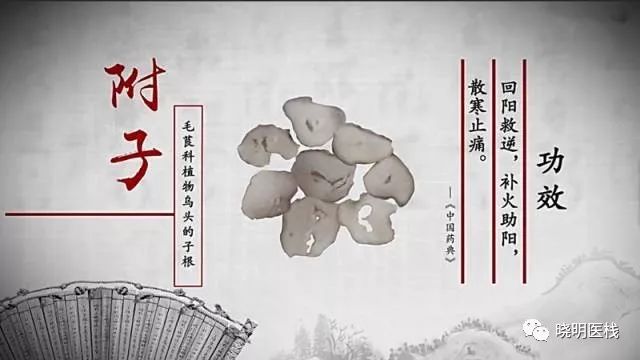

Fuzi, the tuberous root of the Aconitum plant, is documented in the “Shennong Bencao Jing” (Shennong’s Classic of Materia Medica): “It is pungent and warm. It treats wind-cold cough, reverses evil qi, warms the middle, heals metal injuries, breaks up masses, alleviates blood stasis, cold and warmth, and relieves pain in the knees and inability to walk.” Fuzi is known as the “Number One Herb for Rescuing Yang” in traditional Chinese medicine, and modern physician Wu Peiheng, a representative of the ‘Fire God School’, ranks it as the “Top General of Chinese Medicine”.

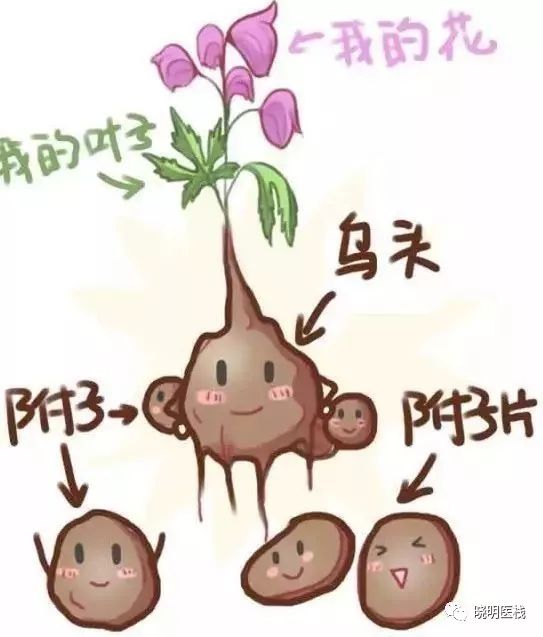

The mother root of Fuzi is called Wutou. Li Shizhen states: “Initially, it is called Wutou, resembling the head of a crow. Fuzi grows attached to Wutou, like a child attached to its mother. Wutou resembles yam, while Fuzi resembles yam seeds; they are essentially the same plant.” Fuzi is propagated through its tuberous roots. If the tuber produces lateral roots, it is called Wutou, while the attached lateral roots are Fuzi; if the tuber does not produce Fuzi, it grows large like a single garlic bulb, and is called Tianxiong. Among the three, Tianxiong has the strongest warming yang effect, as the tuber grows larger without producing Fuzi, thus its warming and tonifying power is more potent. Wutou has the weakest warming power but is effective in promoting circulation, hence it is used more frequently for pain syndromes, such as in Wutou Guizhi Decoction and Wutou Decoction.

1. Growth Characteristics of Fuzi

Jiangyou in Sichuan is the primary production area for Fuzi, where the Fuzi produced is large, with many small claws, sufficient starch content, high oil content, and rich in effective components, emitting a fragrant aroma during processing. The longitudinal cut surface of fresh Fuzi shows distinct chrysanthemum patterns, which are absent in Fuzi from other regions.

Local farmers in Jiangyou plant Fuzi seedlings before the winter solstice, as this is the time when Yang begins to emerge. The seedlings develop uniformly, the tubers grow quickly, are large, and easy to survive; they harvest before the summer solstice, as this is when Yin begins to emerge, and the climate is hot, causing the development of lateral roots to gradually stop, making it the best time for harvesting.

Fuzi is planted at the winter solstice when Yang begins to emerge and harvested at the summer solstice when the three Yangs converge, embodying the full Yang energy of the year. This is why it is called the first essential medicine for supporting Yang, and it truly deserves this title.

2. Historical Development of Fuzi Processing

The processing methods for Fuzi were first seen in the Han Dynasty’s “Shanghan Lun” (Treatise on Cold Damage), where Zhang Zhongjing categorized Fuzi into “raw” and “processed”. The raw method involves “one piece of Fuzi, raw, peeled, and broken into eight pieces”; the processed method involves “one piece of Fuzi, processed, peeled, and broken into eight pieces”, meaning fresh Fuzi is directly burned in ash until thoroughly cooked, referred to as “processed until complete”. This indicates that Zhang Zhongjing had specific methods for using raw and processed Fuzi, and he pioneered the fire processing of Fuzi.

In the Jin Dynasty, there was a method of frying with charcoal, and during the Northern and Southern Dynasties, a method of soaking in Dongliushui (Eastern Flowing Water) and black beans for five days and nights was used. In the Tang Dynasty, there was a honey coating and roasting method, as noted by Sun Simiao in the “Qianjin Yifang”: “(Fuzi) peel, coat with honey, roast until dry, and coat with honey again.”

In the Song Dynasty, methods included water soaking, boiling with ginger, soaking in ginger juice, vinegar soaking, boiling with red beans, and frying with ginger; during the Jin and Yuan Dynasties, some physicians advocated soaking in salt water before processing or soaking in children’s urine before boiling, providing practical evidence for the later production of salt-processed Fuzi.

In the Ming Dynasty, methods were added such as boiling in water, boiling in honey water, boiling with Ba Dou (Croton), and frying with Fang Feng (Siler), salt, and black beans; Li Shizhen stated: “Raw Fuzi disperses, while cooked Fuzi tonifies strongly. Raw Fuzi must be processed according to the Yin method, peeling and removing the navel before use. Cooked Fuzi should be soaked in water, processed until it breaks apart, peeled and cut into slices while hot, and fried until both inside and outside are yellow, removing fire toxins before use. Another method: for each piece, use two qian of licorice, half a bowl of salt water, ginger juice, and children’s urine, boil together overnight to remove toxins.” Here, Li Shizhen proposed based on clinical experience: raw Fuzi has too much toxicity, and if used raw, it must be processed according to Lei Gan’s Yin method to be medicinal, correcting the habit of using raw unprocessed Fuzi.

Zhang Jiebin conducted extensive research on Fuzi processing, primarily using licorice to process Fuzi, explaining the principles, which have significant implications for contemporary research on the detoxification principles of Fuzi: “Using licorice is not strict; generally, adjust the amount of Fuzi, soak in a very concentrated licorice decoction for several days, peel and cut into four pieces, then soak again in concentrated licorice decoction for two to three days until soft and thoroughly soaked, then cut into slices and fry over low heat until nearly dry, ensuring that raw and cooked are uniform; if fried too dry, it becomes too cooked and loses all spiciness, and its heat property is entirely lost. Therefore, if processed too much, it is merely called Fuzi, and its efficacy cannot be verified. The reason for using licorice is that Fuzi’s nature is urgent, and only with licorice can Fuzi’s nature be moderated, and its toxicity be alleviated. If urgent use is needed, wrap it in thick paper, soak in licorice decoction, either stew or roast until soft, then cut open and rewrap, frequently soaking and roasting until cooked to the right degree.”

3. Classification and Evaluation of Traditional Fuzi Processing

Throughout history, various processing methods have been invented to reduce the toxicity of raw Fuzi. However, by the late Ming and early Qing Dynasties, the method of processing with Danba water became standardized, and modern traditional Fuzi processing methods are mostly based on this method.

Jiangyou Fuzi has the characteristic of “overnight rot”; fresh Fuzi dug from the ground may rot overnight. However, soaking Fuzi in Danba liquid can preserve it, making it simple and practical, so the main modern processing of Fuzi involves soaking in Danba water, boiling, and rinsing. Since Danba is a very Yin substance, it can be used to process very Yang substances. Danba also has a solidifying effect; Fuzi soaked in Danba will not disintegrate during steaming or boiling, which is beneficial for the next processing steps.

In traditional Fuzi processing, fresh Fuzi is first cleaned of fibrous roots and soil, then soaked in a high concentration of Danba liquid, and processed as needed.

Traditional Fuzi includes black shun slices, white Fuzi slices, yellow Fuzi slices, and processed Fuzi slices, with the processing steps as follows:

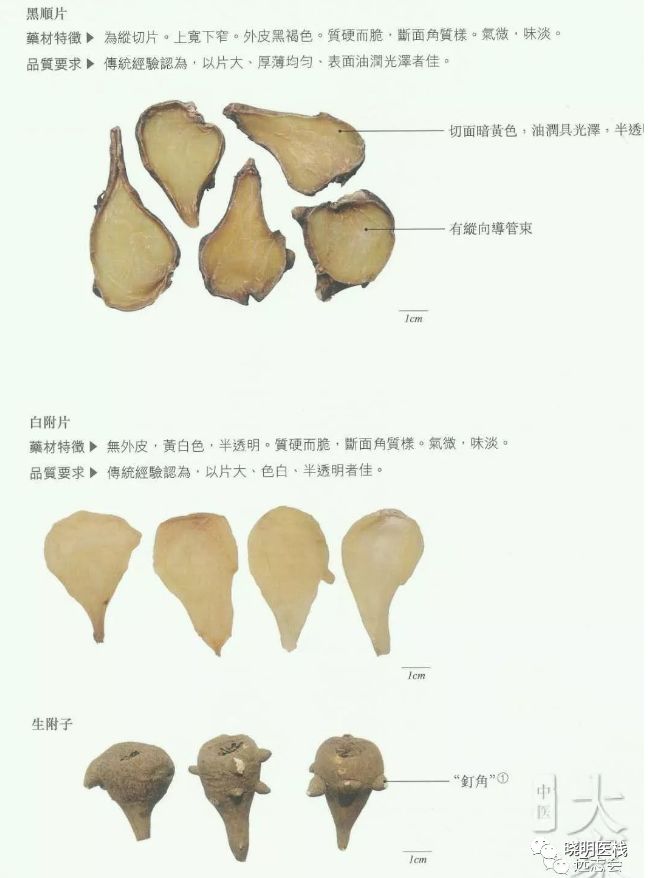

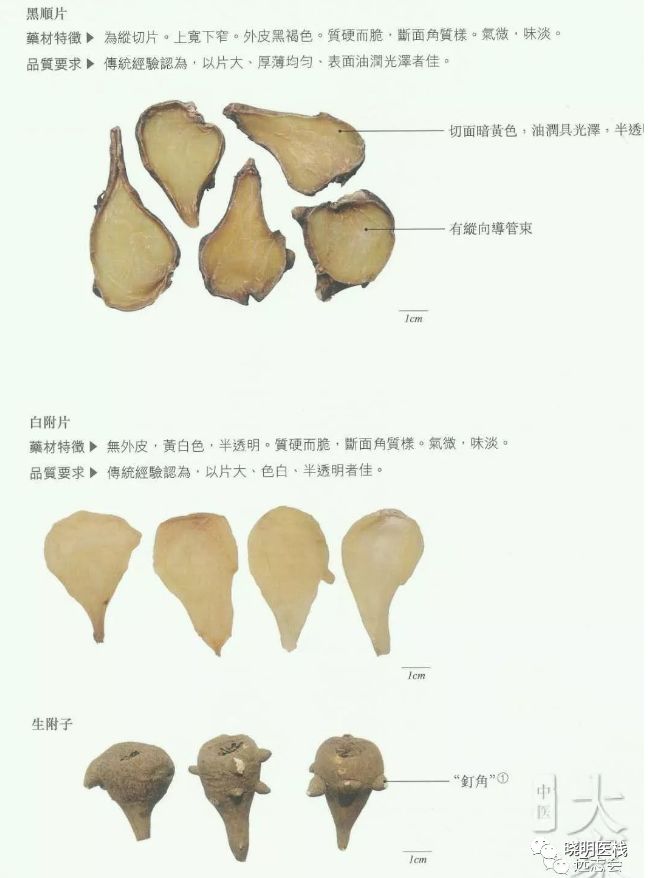

(1) Black Shun Slices: Soak Fuzi in Danba liquid, boil until thoroughly cooked, rinse with water, cut into slices, then dye with coloring agents, and steam until the Fuzi slices show an oily surface, then dry to produce the black shun slices commonly used in hospitals.

(2) White Fuzi Slices: After removing Fuzi from the Danba pool, boil until thoroughly cooked, peel and slice, and rinse with water. Then steam, and finally, dry the steamed Fuzi slices in the sun until half dry, fumigate with sulfur until yellow, and then dry completely, resulting in the yellowish and visually appealing white Fuzi slices, also known as jade Fuzi slices.

(3) Yellow Fuzi Slices: Remove Fuzi from the Danba pool, boil until thoroughly cooked, slice, and dry, resulting in yellow Fuzi slices. Yellow Fuzi slices have not undergone the Danba soaking process, so they have higher toxicity and are relatively cheaper; most drugstores sell this type of yellow Fuzi slices.

(4) Processed Fuzi Slices: Remove Fuzi from the Danba pool, slice, dry until half dry, then mix with sand and fry at high temperature until charred yellow, hence also called fried Fuzi.

4. Evaluation of Traditional Fuzi Processing

Although there are many types of soaking methods for Fuzi, the processed Fuzi (black shun slices, white Fuzi slices, yellow Fuzi slices) are all referred to as processed Fuzi slices.The processing of Fuzi mainly focuses on detoxification, as the toxicity of Fuzi primarily comes from the alkaloids contained in it. Therefore, various processing methods are mostly used to reduce the content of these alkaloids, but these alkaloids are both toxic components and effective medicinal ingredients.Zhang Zhongjing’s use of raw Fuzi in the Si Ni Decoction and similar formulas for treating critical conditions with weak pulse and declining Yang energy, demonstrates that raw Fuzi possesses pungent, warm, and strong heat properties, capable of rescuing Yang, warming and tonifying kidney Yang, dispelling cold, and alleviating pain. Thus, for over a thousand years, it has been one of the important formulas for rescuing critically ill patients.

Traditional Fuzi processing methods generally involve steaming and rinsing repeatedly. Through this processing process, the effective components of Fuzi (alkaloids) are largely lost with the rinsing water, making it safer for medicinal use, but Fuzi may have become ineffective, which could be one reason why many people find Fuzi slices ineffective.Another serious issue with the traditional Danba processing method is that Danba poses significant harm to the human body. The processed Fuzi slices on the market, especially yellow Fuzi slices, contain no less than 10% Danba, which is calcium chloride, widely used in industrial production. Although Danba is also used in food, such as in tofu, the dosage is very small and nearly harmless to the human body. However, processed Fuzi slices differ, as almost all processed Fuzi slices retain large amounts of Danba, which is highly toxic.

Excessive Danba residue in processed Fuzi can cause a burning sensation in the stomach (often mistakenly thought to be caused by the heat of Fuzi slices); it can also suppress the central nervous system, leading to symptoms such as dizziness, headaches, and diarrhea (often mistaken for detox reactions); furthermore, Danba can coagulate proteins, and excessive intake can lead to blood coagulation and even death.

The symptoms of Danba poisoning are very similar to those of Aconitine poisoning, leading to clinical misdiagnosis of Danba poisoning from low-quality Fuzi containing high levels of Danba as Aconitine poisoning, causing many people to fear Fuzi.

Aconitine poisoning generally presents with numbness of the tongue, limbs, or even the whole body, palpitations, dizziness, diarrhea, and sweating. For general poisoning symptoms, drinking rice washing water, brown sugar water, or honey water, or decocting licorice soup can usually relieve symptoms within fifteen minutes to half an hour. In severe cases, if coma occurs, hospital rescue is necessary.

Additionally, there are other methods to detoxify raw Fuzi besides processing; combining Fuzi with other herbs can also reduce toxicity and enhance efficacy. For example, in the “Shanghan Lun”, Si Ni Decoction and Ganjiang Fuzi Decoction, the combination of Ganjiang (Dried Ginger) and Fuzi not only enhances the effects of rescuing Yang and warming the middle but also reduces the toxicity of Fuzi. Modern pharmacological studies show that when Fuzi is decocted with Ganjiang and licorice, not only is the content of three toxic alkaloids in Fuzi reduced significantly, but the cardiotonic effect of Fuzi is also markedly enhanced.