There is a type of medicinal formulation that seems rarely used in daily life, yet authors of martial arts novels seem to have a fondness for it, often depicting it as a notorious poison in the martial world. For instance, the Shixiang Ruojin San from Heavenly Sword and Dragon Slaying Sabre, a poison given to Zhao Min, the daughter of the King of Ruyang during the Yuan Dynasty, by a monk from the Western Regions. This poison is colorless and odorless, causing the victim’s muscles and bones to weaken, rendering them unable to use their internal energy. The poison and its antidote appear identical, and if the poisoned person consumes more poison, they will die instantly. Another example is the Sanxiao Xiaoyao San from Demi-Gods and Semi-Devils, which is commonly used by the Xingxiu Sect. It is made from poisonous snakes, scorpions, centipedes, toxic toads, and poisonous spiders. Those affected by the Sanxiao Xiaoyao San will emit a strange laugh unknowingly, and after laughing three times, they will die immediately. The Wudu San is a hidden weapon in Liang Yusheng’s martial arts novels, made from five toxic substances: golden leaf chrysanthemum, black heart lotus, peach blossoms contaminated with miasma, wisteria from the cold blue pool in Miaojiang, and the ashes of the green silkworm. This highly toxic poison does not manifest symptoms immediately, but after forty-nine days without an antidote, the victim will suffer from severe decay and die, experiencing more pain than from a snake bite. It seems that this formulation is not a good thing at all. Today, I will introduce this ancient formulation—Sanji (powder formulation)—which, despite its lethal portrayal in literature, has many advantages.

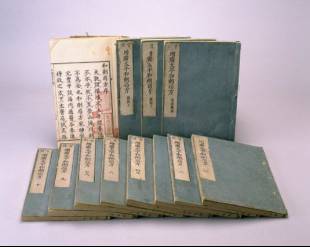

The Sanji is one of the earliest formulations used in Chinese medicine, with a long history. During the period of the Neijing, it was considered one of the four basic formulations: Wan (pills), San (powders), Gao (plasters), and Dan (elixirs). Sanji is typically used in traditional Chinese medicine formulations, referring to powdered preparations made from medicinal materials or their extracts that have been crushed and mixed evenly. The Chinese Pharmacopoeia (2015 edition) has recorded over 50 types of Chinese medicinal powders, such as Qili San (Seven-Parts Powder) and Bamei Qingxin Chenxiang San (Eight-Flavored Fresh Agarwood Powder). In modern medicine, due to the development of solid dosage forms like tablets and capsules, chemical drug powders are rarely seen; the Chinese Pharmacopoeia (2015 edition) only lists three, such as Taurine San and Phosphomycin Ammonium Trihydrate San.

Classification of Sanji

By purpose: It is divided into internal and external powders. Internal powders are further divided into Tiao San (adjusted powders) and Zhu San (boiled powders). Tiao San is made into fine powder and taken with tea, wine, honey, warm water, or hot porridge, such as Chuanxiong Chajiao San (Chuanxiong Tea Powder) and Qili San; Zhu San involves wrapping the powder in cloth and boiling it, with distinctions between fine and coarse powders, such as Yi Yi Fu Zi Bai Jiang San (Coix and Aconite Powder) and Ren Shen Bai Du San (Ginseng Powder for Expelling Pathogenic Factors). External powders include those for application on the skin or mucous membranes, powders for blowing into nasal or ear cavities, dental powders (also known as tooth powder) for cleaning teeth or treating dental diseases, and insecticidal powders for killing fleas, lice, and bedbugs.

By composition: It is divided into single powders (composed of one medicinal substance) and compound powders (composed of two or more medicinal substances).

By dosage: It is divided into divided-dose powders and undivided-dose powders. Divided-dose powders are packaged according to single doses, while undivided-dose powders are packaged according to total doses for multiple uses.

By nature: It is divided into general powders and special powders. Special powders include those containing toxic substances, low-melting mixtures, liquid-containing powders, and ophthalmic powders.

Researchers have found that during the pre-Qin, Han, and Song dynasties, the most frequently recorded formulation type in major medical texts was the Sanji, followed by decoctions, pills, and plasters. The Wushier Bingfang is currently the earliest known formula book in China, with the largest number of Sanji formulations, although it does not explicitly mention the term Sanji, such as “One formula: powdered peony, half a cup, take a pinch the size of three fingers.” The Huangdi Neijing also records Sanji, such as “Take 10 parts of Ze Xie and Shu, and 5 parts of Mi Xian, mix into a pinch for the last meal.” During the Eastern Han period, the form of medicinal decoctions was “(mouth father) chewed,” and Pang Anshi explained in the Shanghan Zongbing Lun: “All decoctions that say (mouth father) chewed refer to the coarse powder form, which is what we call coarse powder today.” The Shanghan Zabing Lun contains many Sanji, and it was the first to propose the term San, such as Wuling San, Si Ni San, Guati San, Mu Li Ze Xie San, Dang Gui Chi Xiao Dou San, and Dang Gui Shao Yao San, which are still in clinical use today.

The most famous and influential Sanji in history is likely the Wushi San, also known as Han Shi San. It was recorded as early as in the Records of the Grand Historian in the biography of Bian Que, indicating that the use of Wushi San may have existed during the pre-Qin and Western Han periods, as a self-treatment method for physicians that required differentiation and treatment. Baopuzi records its composition as “cinnabar, realgar, white alum, green lead, and stone of compassion.” The Guisi Cungao states: “The Tongjian Zhu says that Han Shi San originated from He Yan. It is also said to be made from refining stalagmite and cinnabar, which can avoid fire food, hence called cold food. According to cold food, the food should be cool, and clothing should be thin, only slightly warm wine is to be drunk, not hot food. Its method is based on the Jinkui Yaolue.” The Shishuo Xinyu states: “Taking Wushi San not only treats diseases but also makes one feel enlightened.” As the metaphysics flourished during the Wei and Jin dynasties, Wushi San became a common health product among scholars and literati. If one were to say which ancient dynasty is most similar to modern times, I would certainly say the Wei and Jin dynasties, where scholars indulged in drugs, ran wild, and acted recklessly. During the Jin dynasty, the use of Wushi San reached its peak, and Lu Xun specifically wrote about the relationship between the Wei and Jin style and the use of drugs, wine, and literature, noting that the influence of Wushi San was comparable to that of opium in the late Qing dynasty, as the Wei and Jin literati dressed loosely, wore wooden sandals, and let their hair down, all related to the use of Wushi San.

By the Song dynasty, due to the government’s strong promotion, the application of Sanji reached its peak, and the decoctions of the Han and Tang dynasties were almost completely replaced by boiled powders during this period. The Dream Pool Essays states: “In ancient times, decoctions were used the most, while pills and powders were rarely used. In recent times, decoctions are rarely used, and all decoctions are now boiled powders.” The boiled powder is both a traditional method of preparing Chinese medicine and one of its formulations, which involves first making the medicinal materials into powder, then boiling them in water, either straining out the residue or taking it with residue, using water as a solvent to extract the juice from the medicinal particles or fine powder. It is now generally considered to belong to the category of Sanji.

From the Taiping Huimin Heji Ju Fang, we can also see examples of the prevalence of boiled powders. Although some formulas are still named as certain decoctions or pills, the actual method of administration is boiled powder, such as the preparation method for Bai Hu Tang in the Taiping Huimin Heji Ju Fang: “Grind into fine powder, take three qian, add one and a half cups of water, and boil with over thirty grains of polished rice until reduced to one cup, strain out the residue, and take warm.” The preparation method in the Sheng Ji Zong Lu states: “Take the four ingredients, coarsely crush and sift, take five qian, add one cup of water, and boil down to seven parts, strain out the residue and take warm.” “Tang” means to wash away, used for major illnesses, while decoctions are liquid formulations, the oldest and most widely used in clinical practice, absorbed quickly, and can exert their effects rapidly. “San” means to disperse, used for acute illnesses, while powders are solid formulations that can be taken with warm water or boiled, easy to prepare, absorbed quickly, and save medicinal materials. Both decoctions and powders have their advantages; why did many decoctions change to powders during the Song dynasty?

The Su Shen Liang Fang records: “For boiled powders, the maximum amount is just three to five qian. In terms of efficacy, how can it compare to decoctions? However, since it is powerful, it should not be wasted. The dosage must be appropriate, and it is difficult to make a definitive conclusion.” This indicates that people at that time believed that the efficacy of boiled powders could rival that of decoctions, and the dosage of boiled powders was smaller than that of decoctions. After the traditional decoctions were converted to boiled powders, there was no significant difference in effect, and in terms of the amount of medicinal materials used, the dosage of boiled powders was significantly less than that of decoctions, achieving the same effect as the decoction group. Traditional decoctions showed disadvantages such as waste of medicinal materials and high costs, which are not conducive to the development of traditional Chinese medicine. In contrast, if boiled powders were widely promoted, it would greatly save medicinal materials and economic costs.

The famous physician of the Northern Song dynasty, Pang Anshi, wrote in his Shanghan Zongbing Lun: “Anshi believes that during the Tang dynasty, due to the An-Shi Rebellion, the local warlords were rampant, and by the Five Dynasties, the transportation of medicinal materials was scarce, so physicians rarely used decoctions and mostly used boiled powders… During the reign of Emperor Huanyou, ginseng was priced at 240 to 250 wen per two, while white atractylodes was priced at over ten wen per two. Now it has increased to four to five hundred. The production areas are not continuous, and the common people plant seeds to gain substantial profits, which indicates that the land is becoming less fertile, and the production of medicinal materials is decreasing. The preparation of decoctions has suffered due to the long-term chaos in the world, and during times of thin land and numerous natural disasters, how could one not be frugal and resort to boiled powders?” The Song dynasty experienced the An-Shi Rebellion and rampant warlords during the Tang dynasty, and the Five Dynasties were marked by fragmented power, transportation disruptions, and a shortage of medicinal materials. By the Song dynasty, the use of medicinal materials was extremely wasteful, coupled with poor land and low production, leading to insufficient medicinal materials for medical use. Under these conditions, how could one not be frugal with the dosage of medicinal materials, abandoning the large doses of decoctions and being forced to use the smaller doses of boiled powders? Processing medicinal materials into powders is the most cost-effective method, easy to store, convenient for transportation, and simple to take, meeting historical needs, thus leading to the widespread use of boiled powders in medicine.

After the Song dynasty, with the development of productivity and an increase in the supply of medicinal materials, specialized “raw medicinal pieces” production workshops emerged, known as “Xiuhe Yaosuo” (medicinal processing workshops). In pursuit of greater economic benefits, the production of coarse powders decreased, and with the increasing intensity of medicinal processing, the form of medicinal pieces emerged and was applied. The Su Shen Neihan Liang Fang noted that the coarse powders led to “difficulties in identifying medicinal materials.” After the Qing dynasty, there was a one-sided emphasis on “authentic medicinal materials,” and medicinal pieces became the mainstream formulation for decoction use due to their ease of identification and quality assessment, thus gradually replacing coarse powders after the Jin and Yuan dynasties. After the Ming and Qing dynasties, the use of boiled powders became increasingly rare, and the use of decoctions gradually recovered.

In modern times, the application of boiled powders has nearly disappeared, but many researchers still advocate for their use. For instance, Pu Fuzhou criticized the practice of converting effective small-dose boiled powders into large-dose decoctions, stating, “Yupingfeng San is a formula for treating elderly individuals or those with Wei deficiency who are prone to colds, using three to five qian of coarse powder for decoction, with satisfactory results. Some use large-dose decoctions, which cause chest fullness and discomfort after three doses, but switching to small-dose boiled powders yields effective results without the issue of chest fullness… For chronic diseases, I recommend boiled powders to adjust what is deficient and supplement what is lacking.”

The Sanji originated in the pre-Qin period, flourished during the Han dynasty, peaked during the Tang and Song dynasties, and declined during the Ming and Qing dynasties, playing a crucial role in the long development of Chinese medicine. With the advancement of modern pharmaceutical technology, the preparation of boiled powders has become simple and rapid. As an essential traditional formulation, Chinese medicinal boiled powders not only retain the characteristics of traditional decoctions but also are small in quantity yet potent, offering significant economic and social benefits. In light of the current challenges of scarce medicinal resources and rising prices, promoting the use of boiled powders could be a viable solution. However, there may be various issues in production, processing, storage, and usage during implementation, so further research is needed for the promotion and application of boiled powders.

Long press the image above for 3 seconds to scan the QR code and follow us

If you like it, please give us a thumbs up! ↙