Author: Li Shuang

The Aesthetic Beauty of ‘Mutual Generation of Emptiness and Fullness’

The history of Chinese painting is long and profound, and its aesthetic beauty of ‘mutual generation of emptiness and fullness’ holds immeasurable value in aesthetics and artistic form. ‘Mutual generation of emptiness and fullness’ harmonizes the layout of the artwork, using emptiness to contrast fullness and vice versa, creating an immersive experience for the viewer.

This concept is also reflected in ancient literature, where the technique of using emptiness to highlight fullness and fullness to highlight emptiness is employed to express emotions. In Yang Wanli’s poem “Sending Lin Zifang at Dawn from Jingci Temple,” it states: “The lotus leaves stretch endlessly to meet the sky, the lotus flowers bloom red under the sun.” This describes the beautiful scenery of West Lake in June, where dense lotus leaves layer upon each other connecting with the blue sky, and the vibrant lotus flowers stand out against the green leaves, appearing particularly bright and beautiful. The scenery depicted is real, while the poet’s feelings of longing for a friend are abstract; the poem does not explicitly mention the sorrow of parting, yet readers can feel the poet’s affection for his friend through the lines. This is an example of expressing emotions through scenery, embodying ‘mutual generation of emptiness and fullness’ by using objects to reflect human feelings.

The concept of ‘mutual generation of emptiness and fullness’ is also evident in calligraphy, where the ink lines and the spaces left blank represent this duality. The black ink left by the brush is the fullness, while the blank spaces are the emptiness; the combination of emptiness and fullness forms the characters. The pressure of the brush, the amount of ink, and the dryness of the ink represent the emptiness, while the moist areas represent the fullness. A calligraphy work, whether from the perspective of creation or appreciation, must approach from the angle of ‘mutual generation of emptiness and fullness’ to better grasp the subtleties of calligraphy.

Chinese traditional opera culture is profound and extensive; in opera, actors use actions, singing, and dialogue to evoke imagery in the audience, creating an immersive experience. The stage settings in opera are minimal, relying primarily on the actors’ performances to convey the scenes. In the farewell scene of “Butterfly Lovers” (Liang Shanbo and Zhu Yingtai), the stage is sparsely set, depending on the actors’ singing to express Liang Shanbo’s deep feelings for Zhu Yingtai; the environment is the emptiness, while the emotions of farewell are the fullness. The ‘mutual generation of emptiness and fullness’ in opera is based on reality, not merely imitating real life, but selecting, exaggerating, and beautifying life, using a virtual environment and the actors’ skills to draw the audience into the scene.

In traditional Chinese painting, the combination of emptiness and fullness generates the artistic effect of ‘mutual generation of emptiness and fullness’, maximizing the expression of both. In Chinese painting, there is no part that lacks the relationship of emptiness and fullness; any opposing unity in the artwork can be reduced to this concept, such as density and sparsity, light and heavy, black and white, thick and thin, etc. To give the entire work a grand yet delicate feeling, the technique of ‘mutual generation of emptiness and fullness’ must be employed. Regardless of the expressive techniques used, they cannot escape the unity of emptiness and fullness, as well as their mutual transformation. It can be said that ‘mutual generation of emptiness and fullness’ is the most important expressive technique in traditional Chinese painting.

Specific Expressions of ‘Mutual Generation of Emptiness and Fullness’ in the Aesthetic of Chinese Painting

(1) ‘Mutual Generation of Emptiness and Fullness’ Harmonizes the Layout of the Painting

The application of ‘mutual generation of emptiness and fullness’ in Chinese landscape painting is primarily reflected in composition. Landscape painting mainly depicts natural scenery, unifying various opposing elements within the artwork to form a harmonious picture. The Northern Song artist Guo Xi proposed the concept of “three distances,” later supplemented by Han Zhuo with “broad distance, secluded distance, and confusing distance,” collectively known as the six distance methods. If the treatment of the empty spaces in the painting is improper, the real scenes will be affected, and the entire painting will lack unity. The principle of positioning in Xie He’s six laws emphasizes the importance of composition; only by properly handling the emptiness and fullness in the painting can harmony and unity be achieved.

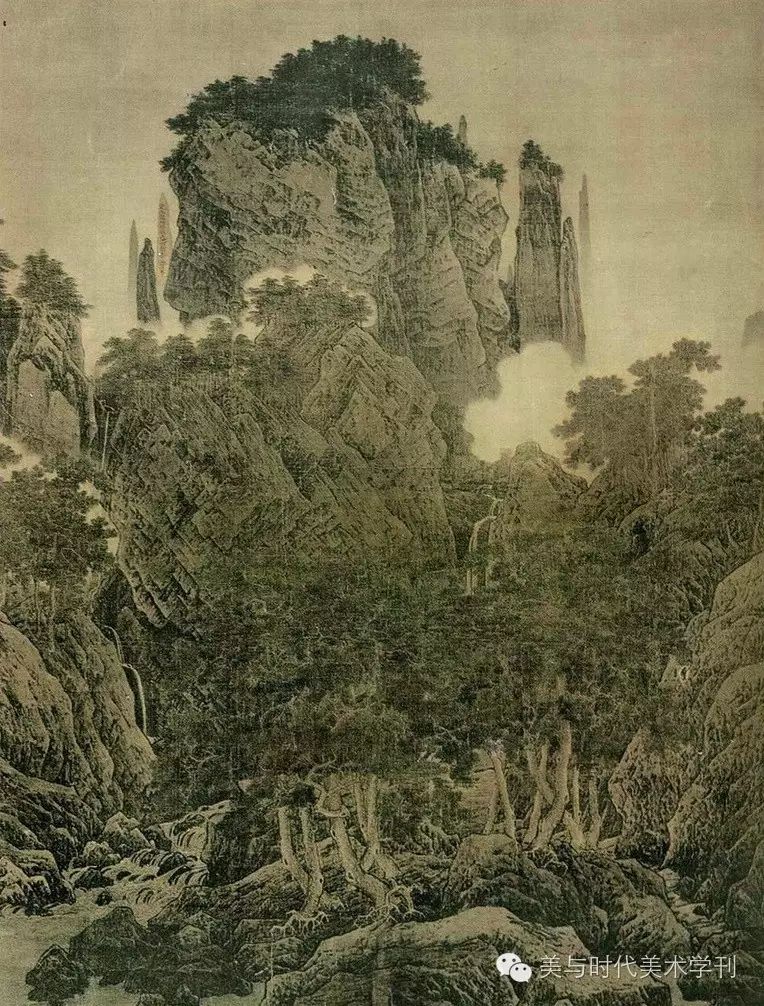

In Song dynasty landscape paintings, the clever use of mist creates a contrast between emptiness and fullness, achieving overall harmony. Li Tang’s “Pine Wind in Ten Thousand Valleys” from the Southern Song depicts the misty pines and clear streams of Jiangnan, with winding ridges lined with pine forests, clouds rising in the valleys, and a watermill nestled beneath the mountains, with a wooden bridge crossing the stream. The panoramic composition expresses layers of depth through the surrounding pine forests, while the clouds at the mountain’s waist delineate the layers, ensuring a balanced density in the painting. Huang Gongwang’s “Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains” from the Yuan dynasty exemplifies the arrangement techniques of Yuan artists, emphasizing that mountains should be larger than trees, and trees larger than people, while the main peak highlights the distant peaks, enhancing the sense of space. Yuan artists focused on foreground scenes, depicting mountains, rocks, and trees, extending beyond one-third of the painting, then separating the middle ground with water, pushing the middle ground to the opposite bank, creating a sense of separation, referred to as broad distance. The virtuality of the middle ground water contrasts with the reality of the foreground, expanding the entire painting, making the foreground and background more harmonious and enhancing the grandeur of the landscape painting.

In the Song dynasty, Cui Bai’s “Double Happiness” depicts withered branches and leaves swaying in the cold wind on a nearby hillside, with two mountain birds calling to a mountain hare, which is startled and looks back. The background is empty, primarily highlighting the mountain hare and the two birds, conveying the desolation of late autumn. The emptiness in the background accentuates the bleakness of autumn and the ethereal quality of the mountains, allowing the abstract imagery to manifest in the painting, further highlighting the dynamics of the three animals, creating a unified visual experience without overwhelming the viewer. In Ma Yuan’s “Plum Stone Stream and Birds,” the large blank space on the right emphasizes the dynamic of the water birds playing freely, ensuring the entire painting is rigorous, unified, and harmonious. In Chinese painting, only by correctly handling the position of emptiness can the aesthetic beauty of the entire painting be expressed, thus preserving the essence of Chinese painting.

(2) ‘Mutual Generation of Emptiness and Fullness’ Creates a Sense of Space in the Painting

In the history of Chinese painting, the technique of ‘mutual generation of emptiness and fullness’ was mastered early on. The Eastern Jin artist Gu Kaizhi’s “Admonitions of the Instructress to the Court Ladies” is an illustration based on Zhang Hua’s work, where Gu Kaizhi creates a series of captivating figures, with a background that is empty to highlight the identities and grace of these ancient court women. The “Emperor Taizong Receiving the Tibetan Prime Minister” depicts the scene of Emperor Taizong of the Tang dynasty receiving the Tibetan Prime Minister Lu Dongzan, where the background is left empty to emphasize Emperor Taizong as the main character, discarding many intricate props to focus on the portrayal of the characters’ likeness and attire. On the right side of the painting, Emperor Taizong is surrounded by palace maids, showcasing the dignity of the emperor. The dense crowd and the intricate clothing patterns form the fullness in the painting, while the simplicity on the left contrasts with the complexity, creating a sense of space.

Guo Xi’s “Early Spring” from the Song dynasty depicts the vitality of nature awakening in early spring, with the joy of the artist permeating the entire painting. The main peak rises into the clouds, with secondary peaks responding on either side, and the mountains are shrouded in mist, while the trees and rocks are meticulously detailed. The contrast between the virtual background and the real foreground enhances the sense of space, further expressing the vitality of early spring.

In Ni Zan’s “Six Gentlemen,” the composition is divided into two parts, with the foreground featuring six different types of trees as the main subject, the middle ground being an empty river surface, and the background being distant mountains. This exemplifies Ni Zan’s technique of broad distance, showcasing the interplay of distant mountains, river surface, and trees, enhancing the sense of space in the entire painting, thus reflecting Ni Zan’s artistic style.

In a single work, the interplay of emptiness and fullness is both opposing and unified, using emptiness to highlight the rhythm of fullness and fullness to accentuate the ethereal quality of emptiness. ‘Mutual generation of emptiness and fullness’ strengthens the layering of the entire work, enhancing the sense of space, allowing viewers to clearly perceive the emotions and aesthetic beauty the artist wishes to convey.

(3) ‘Mutual Generation of Emptiness and Fullness’ Expands the Aesthetic Beauty of the Painting

In a single work, the virtual and real realms are mutually opposing yet interdependent. The real realm is what we can see, while the virtual realm, in contrast to the real, leaves space for the viewer’s imagination; in landscape painting, the importance of the virtual realm surpasses that of the real.

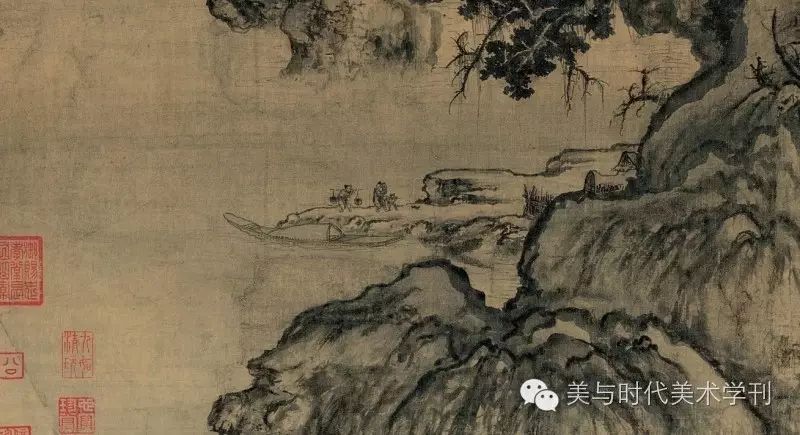

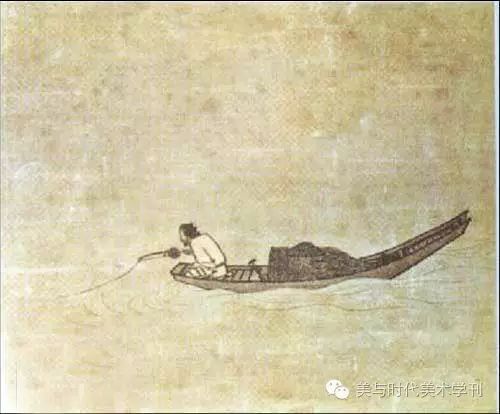

Song dynasty artist Xia Gui, known as “Xia Banbian,” painted “Pine Creek Boating,” where the foreground features a pine tree, and the distance shows people boating, with the rest being blank, using the real scene to highlight the distant virtual scene. The blank spaces in this painting include both the water surface and the sky, evoking thoughts of a vast sky under which people are boating on a shimmering, expansive water surface. Song dynasty artist Ma Yuan, known as “Ma Yijiao,” painted “Fishing Alone in the Cold River,” where a small boat and an old man fishing are depicted in a large blank space, with a few strokes representing the water waves. The emptiness in the painting allows for limitless imagination, conjuring images of a boundless lake and distant misty mountains, with only the old man fishing in the tranquil waters.

In Ni Zan’s “Autumn Clearing at the Fisherman’s Lodge,” the foreground features a small area of scattered rocks and a few ancient trees, with distant mountains above and an expansive river surface in the middle, creating a sense of quiet desolation and ethereal mist. The blank space in the middle evokes thoughts of the autumn scenery of Jiangnan, leaving limitless imagination and allowing one to appreciate the charm of Jiangnan’s autumn.

From the works of these ancient and modern artists, it is evident that they skillfully employ the technique of ‘mutual generation of emptiness and fullness’ to enhance the aesthetic beauty of their paintings, using emptiness to highlight fullness, allowing viewers to immerse themselves in the artistic essence of the entire work.

Conclusion

‘Mutual generation of emptiness and fullness’ not only holds significant artistic value in aesthetics and artistic form but also maintains the essence and national character of Chinese painting in the face of Western cultural impact and the baptism of world culture, possessing immeasurable practical significance. In Chinese painting, emptiness and fullness are not merely formal contrasts; they infuse the artist’s genuine emotions into the artwork through this formal beauty, allowing viewers to feel the aesthetic beauty of the painting’s essence. Through the study of ‘mutual generation of emptiness and fullness’ in Chinese painting, we must not only recognize the cultural spirit of emptiness and fullness expressed in Chinese painting but also appreciate the emotions conveyed by the artist’s expression of emptiness and fullness.

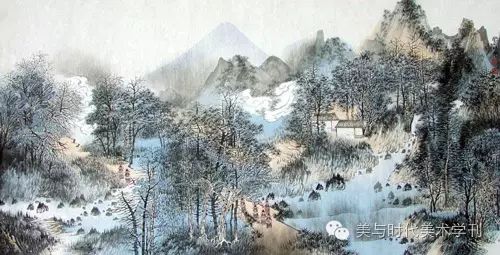

From the purposeless transmission of emptiness and fullness in ancient paintings to the continuous research by artists on this concept, and to the inheritance and development of ‘mutual generation of emptiness and fullness’ by modern artists, the aesthetic beauty created by emptiness and fullness is not only a concrete manifestation of traditional Chinese philosophy but also a harmonious unity of form and spirit, emotion and scenery, poetry and painting, thus creating the aesthetic beauty of ‘mutual generation of emptiness and fullness’ in Chinese painting.

END

Submission

Email: [email protected]

Submission Address: 98 Jing San Road, Zhengzhou City

Contact Number: 0371-65511020

Scan the QR code

Follow for more exciting content