Introduction: In Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), the concept of syndromes (zhenghou) fundamentally reflects the internal imbalance of Yin and Yang, the dynamics of Zheng (correct) and Xie (evil) energies, and other functional changes related to the characteristics of diseases. It serves as a comprehensive diagnostic concept that encapsulates the causes, nature, location, scope, and dynamics of pathological elements of diseases.

Using modern hierarchical analysis to explore the structural laws of syndromes, TCM syndromes have a core, basic (or fundamental) components, and positioning markers, along with various specific syndromes composed of these elements, ranging from simple to complex. Generally speaking, the pathological mechanisms and symptoms such as Xu (deficiency), Shi (excess), Han (cold), Re (heat), Qi (vital energy), Xue (blood), Yin, and Yang are the core of syndromes, referred to as “core syndromes.” The pathological mechanisms and symptoms related to the heart, liver, spleen, lungs, kidneys, Wei (defensive Qi), Ying (nutritive Qi), and blood serve as the positioning markers and stage markers of syndromes, which can be viewed as “location syndromes.” Conditions such as Yin deficiency, Qi deficiency, blood deficiency, Yang deficiency, Qi stagnation, Qi counterflow, blood stasis, damp-heat, phlegm turbidity, etc., are more basic components formed from the core, referred to as “fundamental syndromes” or “basic syndromes.” Fundamental syndromes are essentially the most basic TCM diagnostic concepts used to categorize syndromes.

As for more specific syndrome concepts that reveal the nature of the disease and indicate the location of pathological changes, such as Kidney Yin Deficiency, Lung Qi Deficiency, Liver Qi Stagnation, Bladder Damp-Heat, Heat Entering the Ying and Blood, Heat Binding the Yangming, Spleen and Kidney Yang Deficiency, etc., these are “specific syndromes” synthesized from fundamental and location syndromes. Specific syndromes are the more standardized names used in daily TCM practice to express disease diagnostic concepts.

This fundamental syndrome is classified according to modern syndrome classification methods. The modern syndrome classification method was largely developed in the early 1950s. This classification represents an important advancement based on previous understandings, aligns with the developmental history of syndrome concepts, and reflects the needs of the times and certain advancements in classification work. However, when measured against modern scientific classification principles, there are significant gaps, making it difficult to encapsulate the inherent connections and interrelations among various syndrome systems within TCM, and it does not fully meet the requirements of TCM academic development. It has not completely escaped the influence of phenomenological classification methods, still bearing certain artificial characteristics, and has yet to achieve the depth and essential natural classification required, thus failing to adequately reflect the essential characteristics of syndromes and their interconnections.

Therefore, further exploration of more reasonable classification methods is an important task in the study of TCM syndromes.

Fundamental syndromes include Qi Deficiency Syndrome, Qi Sinking Syndrome, Qi Collapse Syndrome, Qi Stagnation Syndrome, Qi Counterflow Syndrome, Qi Obstruction Syndrome, Blood Deficiency Syndrome, Blood Collapse Syndrome, Blood Stasis Syndrome, Blood Heat Syndrome, Blood Dryness Syndrome, Blood Cold Syndrome, Essence Collapse Syndrome, Yin Deficiency with Fluid Deficiency Syndrome, Shen Disturbance Syndrome, Yin Deficiency Syndrome, Yang Deficiency Syndrome, Yin Loss Syndrome, Yang Loss Syndrome, Wind Syndrome, Cold Syndrome, Heat Syndrome, Damp Syndrome, Dryness Syndrome, Fire Heat Syndrome, Phlegm Syndrome, Excessive Evil Toxin Syndrome, Taiyang Syndrome, Yangming Syndrome, Shaoyang Syndrome, Taiyin Syndrome, Jueyin Syndrome, Shaoyin Syndrome, Wei Fen Syndrome, Qi Fen Syndrome, Ying Fen Syndrome, Blood Fen Syndrome.

Qi Stagnation Syndrome

1. Overview

Qi Stagnation Syndrome refers to the obstruction of Qi flow in a certain part of the body, a specific organ, or a meridian, leading to symptoms such as “Qi not flowing smoothly” and “pain due to obstruction.” This is often caused by invasion of pathogenic factors, emotional distress, or external injuries. This syndrome is commonly seen in the early stages of diseases, hence the saying “initial disease is in Qi.” It is classified as a Shi (excess) syndrome.

The main clinical manifestations include: localized distension, fullness, oppression, and pain. The distension and pain may vary in intensity and are often not fixed in location, commonly presenting as stabbing or wandering pain; the distension may appear and disappear; the fullness and oppression may be relieved by belching or passing gas; and it is related to emotional factors; the tongue coating is thin, and the pulse is wiry.

Qi Stagnation Syndrome is commonly seen in conditions such as “stomach pain,” “chest pain,” “abdominal pain,” “hypochondriac pain,” “low back pain,” “dysmenorrhea,” and “depression syndrome.”

This syndrome should be differentiated from “Qi Counterflow Syndrome,” “Qi Stagnation with Blood Stasis Syndrome,” “Qi Stagnation with Diarrhea Syndrome,” and “Phlegm and Qi Interlocking Syndrome.”

2. Differentiation

(1) Analysis of this syndrome

This syndrome presents with clinical variations depending on the location of the pathological changes and the nature of the pathogenic factors. (For Qi Stagnation Syndrome manifested in exogenous febrile diseases, please refer to relevant entries on typhoid and warm diseases; here, the focus is on miscellaneous diseases.) Many conditions can cause pain due to Qi stagnation, for example, “stomach pain” caused by Qi stagnation in the middle jiao, whether due to cold or heat pathogens, or due to Liver Qi invading the stomach, all result from disharmony of stomach Qi and Qi stagnation. If cold pathogens invade the stomach, cold accumulates in the middle, causing stomach Qi to become cold and stagnant, leading to severe stomach pain, preference for warmth and pressure, relief with heat, thin white tongue coating, and tight wiry pulse. The treatment should warm the middle, regulate Qi, and relieve pain, using modified Liang Fu Wan (良附丸). If heat pathogens invade the stomach, heat binds the stomach, causing Qi stagnation and obstruction, leading to stomach pain, thirst, desire for cold drinks, halitosis, oral ulcers, and constipation, with a yellow tongue coating and rapid forceful pulse. The treatment should clear the stomach and drain heat, using modified Tiao Wei Cheng Qi Tang (调胃承气汤). If Liver Qi invades the stomach, Liver Qi stagnation leads to disharmony of stomach Qi, resulting in symptoms of stomach pain, radiating pain to the hypochondria, bitter belching, cold limbs, thin tongue coating, and wiry pulse. The treatment should soothe the liver, relieve stagnation, and harmonize the stomach, using modified Si Ni San (四逆散). Similarly, for chest pain, which is located in the upper body, involving the heart and lungs, if Lung Qi fails to disperse, phlegm-heat obstructs and causes chest pain, symptoms include chest pain with cough and shortness of breath, expectoration of thick yellow phlegm, irritability, yellow greasy tongue coating, and slippery rapid pulse. The treatment should open the chest and relieve stagnation, clear heat and transform phlegm, using modified Xiao Xian Xiong Tang (小陷胸汤) combined with Qian Jin Wei Jing Tang (千金苇茎汤). If heart Qi fails to disperse, chest Yang is obstructed, and turbid Yin accumulates, leading to chest pain, symptoms include pain radiating to the back, chest tightness, palpitations, shortness of breath, white greasy tongue coating, and deep thin pulse. The treatment should open the chest and relieve obstruction, transform phlegm, using modified Guo Lou Xie Bai Ban Xia Tang (栝蒌薤白半夏汤) combined with Diao Dao Mu Jin San (颠倒木金散). For abdominal pain, which refers to the area below the stomach, Qi stagnation in the abdomen is related to disharmony of the stomach and intestines. Clinical manifestations can be due to cold, heat, or food stagnation. If cold accumulates in the abdomen, symptoms include severe abdominal pain, preference for warmth and pressure, cold limbs, diarrhea, clear urine, white greasy tongue coating, and tight pulse. The treatment should warm and disperse cold pathogens, regulate Qi, and relieve pain, using modified Li Zhong Wan (理中丸). If heat binds the abdomen, symptoms include abdominal pain and distension, constipation, fullness that is not relieved by pressure, dry mouth and irritability, yellow dry tongue coating, and deep forceful pulse. The treatment should clear heat and drain the abdomen, using modified Da Cheng Qi Tang (大承气汤). If food stagnation occurs in the large intestine, symptoms include abdominal pain and distension, belching of foul-smelling gas, diarrhea with foul and turbid stools, reduced appetite, yellow thick greasy tongue coating, and slippery rapid pulse. The treatment should resolve food stagnation, using modified Zhi Shi Dao Zhi Wan (枳实导滞丸). For hypochondriac pain, commonly seen in liver and gallbladder disorders, often due to emotional distress leading to Liver Qi stagnation, symptoms include distending pain in both hypochondria, wandering pain, chest tightness, bitter mouth, frequent belching, and symptoms that fluctuate with emotions. The treatment should soothe the liver and regulate Qi, using modified Chai Hu Shu Gan San (柴胡疏肝散). For low back pain, Qi stagnation can be caused by external injuries, often due to improper lifting, leading to localized tenderness and swelling, difficulty in bending and turning. The treatment should promote Qi flow, relieve low back pain, and disperse masses, using modified Tong Qi San (通气散). Additionally, Qi stagnation can lead to “depression syndrome,” often due to emotional distress and Qi stagnation. The “Medical Classics of the Five Depressions” states: “The onset of disease is often due to depression, which means stagnation and obstruction.” This indicates that Qi stagnation and depression are precursors to all depression syndromes. Clinical manifestations primarily include Liver Qi stagnation, with symptoms of depression, irritability, chest and hypochondriac fullness, sighing, belching, poor appetite, irregular menstruation in women, thin greasy tongue coating, and wiry pulse. The treatment should soothe the liver, regulate Qi, relieve depression, and open obstructions, using modified Yue Ju Wan (越鞠丸) or Xiao Yao San (逍遥散). If belching persists, consider adding Xuan Fu Dai Zhe Tang (旋覆代赭汤).

Qi Stagnation Syndrome, aside from pathogenic invasion and external injuries, is commonly seen in internal injuries due to emotional distress. This syndrome is closely related to the liver, which governs the smooth flow and regulation of Qi. If the liver fails to regulate, Qi stagnates and accumulates, and these functions are directly influenced by emotional and mental activities. Therefore, individuals who are emotionally repressed, narrow-minded, easily angered, or sensitive are more prone to this syndrome. In gynecological conditions, as women are primarily governed by the liver, which stores blood and nourishes the Chong and Ren meridians, menstruation occurs regularly, and pregnancy is safe. However, if the liver’s blood storage is affected by its regulating function, Liver Qi stagnation will inevitably lead to dysfunction in blood storage and regulation. Thus, Qi Stagnation Syndrome is also commonly seen in conditions such as irregular menstruation, dysmenorrhea, amenorrhea, pregnancy complications, abdominal pain, swelling, postpartum lochia retention, breast lumps, and insufficient lactation. Regarding local meridians, if they are affected by wind, cold, or damp pathogens, leading to poor Qi circulation, symptoms of Qi stagnation and distension may occur. The “Nanjing” states: “Qi that remains and does not flow is the precursor to Qi disease.” For example, wind, cold, and damp pathogens affecting the joints can lead to symptoms of soreness and pain in the limbs, with limited movement.

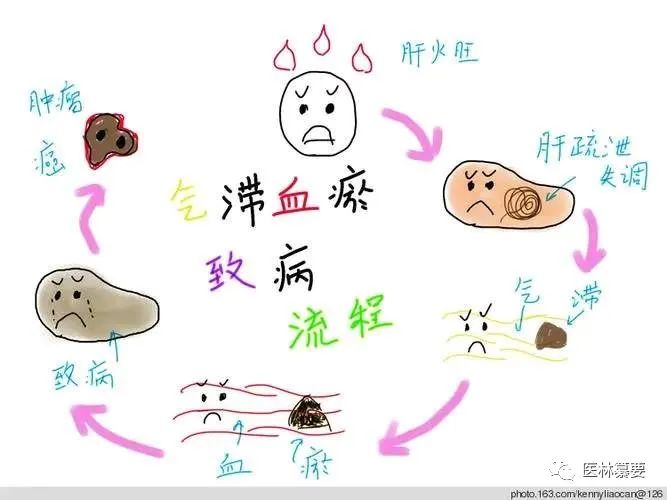

It should also be noted that this syndrome is the most common pathological condition of Qi and serves as the foundation for various Qi diseases. For instance, Qi stagnation can lead to dysfunction in the ascending and descending functions of Qi, resulting in Qi counterflow; Qi stagnation can weaken the spleen and stomach’s ability to receive, digest, and transport, leading to Qi deficiency; Qi stagnation can prevent pathogenic factors from being expelled, leading to excessive evil Qi and transformation into heat; Qi stagnation can disrupt the movement, distribution, and excretion of fluids in the lungs, spleen, and kidneys, leading to edema due to Qi not circulating water, etc. Since Qi and blood share the same source and are mutually rooted in Yin and Yang, Qi diseases can lead to blood diseases, hence the saying “when Qi flows, blood flows; when Qi stagnates, blood stasis occurs.” Conversely, where there is blood stasis, the vessels are obstructed, and blood coagulates, leading to Qi stagnation. For example, the condition of accumulation often arises from emotional distress, leading to Qi stagnation and eventually blood stasis. In clinical practice, external injuries often present with localized hematomas, accompanied by symptoms of Qi stagnation and poor meridian circulation. Therefore, the clinical differentiation of this syndrome should be understood from the interdependence and nurturing relationship between Qi and blood, as they have a mutual causal relationship and should not be viewed in isolation.

(2) Differentiation from similar syndromes

(1) Qi Counterflow Syndrome and Qi Stagnation Syndrome

Both are manifestations of Qi pathology. However, Qi Counterflow Syndrome primarily involves the failure of Qi to ascend and descend, characterized by excessive upward Qi movement, with symptoms such as cough, shortness of breath, belching that does not resolve, nausea, and vomiting; Qi Stagnation Syndrome primarily manifests as Qi stagnation, leading to localized pain and distension, with distension being the main symptom, varying in intensity, and often influenced by emotional fluctuations. Therefore, the etiology and pathogenesis of the two are distinctly different, and their clinical presentations are also different, making differentiation straightforward.

(2) Qi Stagnation with Blood Stasis Syndrome and Qi Stagnation Syndrome

Both exhibit symptoms of Qi stagnation, but the former often develops from the latter, presenting with additional signs of blood stasis. For example, in the early stages of distension, it is often Qi stagnation, while in the later stages, it is more likely to be Qi stagnation with blood stasis. Initially, Liver Qi stagnation leads to spleen dampness and water retention, resulting in abdominal distension that is soft to the touch, hypochondriac pain, belching, and poor appetite; in the later stages, blood flow stagnation leads to abdominal distension that is hard and full, hypochondriac pain that does not shift, abdominal muscles tensing, dark complexion, red palms, and purplish tongue. In the early stage, the treatment should focus on promoting Qi and transforming water to attack the pathogen; in the later stage, the treatment should focus on invigorating blood, resolving stasis, promoting Qi, and addressing both attack and tonification, making differentiation easy.

(3) Qi Stagnation with Diarrhea Syndrome and Qi Stagnation Syndrome

Qi Stagnation with Diarrhea Syndrome, also known as “stagnation diarrhea,” is often caused by damp-heat, epidemic toxins, or excessive consumption of raw and unclean food, damaging the stomach and intestines, leading to dysfunction in the large intestine’s transmission and Qi stagnation. Symptoms include urgency with a feeling of heaviness, abdominal distension, abdominal pain, and diarrhea with red and white stools, yellow or white tongue coating, and slippery rapid or soft pulse. The key points for differentiation from Qi Stagnation Syndrome are: 1. Both can be caused by cold or heat pathogens affecting the intestines, but Qi Stagnation with Diarrhea Syndrome often accompanies damp-heat. 2. Both can present with abdominal pain, distension, and diarrhea, but Qi Stagnation with Diarrhea Syndrome is characterized by urgency and heavy feeling in the abdomen, and diarrhea with red and white stools. Clinical differentiation should focus on these points.

(4) Phlegm and Qi Interlocking Syndrome and Qi Stagnation Syndrome

Both can arise from emotional distress and Liver Qi stagnation. However, Phlegm and Qi Interlocking Syndrome involves Qi stagnation accompanied by phlegm, while Qi Stagnation Syndrome is primarily due to Liver Qi stagnation. Phlegm and Qi Interlocking Syndrome may present with masses or clinical manifestations resembling a mass. For example, phlegm and Qi interlocking in the neck may form a goiter, with symptoms of soft lumps on both sides of the neck, normal skin color, and changes in size with emotional fluctuations. Another example is Plum Pit Qi, where symptoms include a sensation of obstruction in the throat, with phlegm present, making it difficult to swallow or expectorate. Thus, it differs from the symptoms of Liver Qi stagnation, which presents with hypochondriac distension, chest tightness, chest pain, and belching.

【Selected Literature】

“Suwen: The Great Discussion of True Principles” states: “When wood is obstructed, the people suffer from stomach pain in the heart and stomach.”

“Sources of Miscellaneous Diseases: Various Qi” states: “Qi pain in the Sanjiao indicates disease both internally and externally. The Qi in the human body circulates continuously without stopping, often obstructed by emotional distress, dietary habits, and labor, leading to stagnation in the upper jiao, resulting in chest oppression and pain (treat with Zhi Ju Tang or Qing Ge Cang Sha Wan); stagnation in the middle jiao leads to abdominal and hypochondriac pain (treat with Mu Xiang Po Qi San or Zhuang Qi A Wei Wan); stagnation in the lower jiao leads to hernias and low back pain (treat with Si Mo Tang or Mu Xiang Bing Lang Wan); stagnation internally leads to accumulation and pain (treat with Hua Ji Wan or San Leng San); stagnation externally leads to widespread pain, or swelling, or distension (treat with Liu Qi Yin Zi or Mu Xiang Liu Qi Yin). In summary, all are due to Qi disease.

“Shang Han Lun: General Principles” states: “External invasion of wind and cold injures the Zheng, initially Qi interacts with Qi, and subsequently enters the meridians from Qi.”

“Medical Insights: Low Back Pain” states: “If due to sprains or falls, internal stasis leads to pain upon turning, with black stools and a rough pulse, it indicates blood stasis; Zexian Tang is the treatment. If there is stabbing pain that comes and goes, with a wiry pulse, it indicates Qi stagnation; treat with Ju He Wan.”

“Jing Yue Quan Shu: Accumulation” states: “All tangible forms are due to stagnation of food or retention of pus and blood; all juices that coagulate into masses are classified as accumulation, mostly occurring in the blood aspect, where blood is tangible and static. All intangible forms may be distended or not, painful or not, and may appear and disappear with touch; these are classified as accumulation, mostly occurring in the Qi aspect, where Qi is intangible and dynamic.”

“Jufang Huifai: Stagnation Diarrhea” states: “In diarrhea, whether food is digested or not, there is no effort required, only a feeling of fatigue. If it is stagnation diarrhea, it is different, with symptoms of pus or blood, or a mixture of pus and blood, or intestinal residue, or a mixture of residue and dregs, with varying degrees of pain or no pain, but all have urgency and heaviness…”

This article is authored by Hu Guoqing, selected from the “Differential Diagnosis of TCM Syndromes” edited by the Chinese Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine, with Yao Naili as the chief editor and Zhu Jianguo and Gao Ronglin as deputy editors. Copyright belongs to the relevant rights holders. This public account is used for academic exchange only. If there is any infringement, please contact the editor for deletion.