This

class

breaks

down

The weather is getting cooler, and with less irritability, one can quietly read and practice calligraphy. Recently, I seem to have gained some insights into ‘虚’ (Xu) and ‘实’ (Shi). This week, let’s discuss ‘虚’ and ‘实’.

‘虚’

is a large mound. The Kunlun mound is referred to as Kunlun Xu. In ancient times, nine families made a well, four wells made a town, and four towns made a mound. The mound is referred to as ‘虚’. It is derived from the sound of ‘丘’ (qiū) (from Shuōwén Jiězì).

The character ‘虚’ is explained in Shuōwén Jiězì as ‘a large earth mound’, which differs somewhat from our understanding today. It then mentions that ‘Kunlun mound is called Kunlun Xu’, indicating that in ancient texts, ‘虚’ and ‘丘’ express the same meaning. The next sentence, ‘In ancient times, nine families made a well, four wells made a town, and four towns made a mound’, comes from the ‘Zhou Li’ and discusses an ancient land system called ‘井田制’ (jǐngtián zhì). The ‘井田制’ was formed in the Shang Dynasty and matured in the Western Zhou, but this system collapsed during the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods.

In ancient times, land measuring one hundred steps in length and width was divided into one ‘田’ (tián), cultivated by one adult laborer. Nine such fields combined formed a ‘井’ (jǐng) shape, hence ‘nine families made a well’. Another interpretation is that nine families shared a well for drinking water, akin to an ancient rural commune, leading to ‘four wells made a town, four towns made a mound’. Here, ‘丘’ also expresses a land concept. There are various interpretations of the ‘井田制’, which essentially refers to rural land ownership, where farmers had cultivation rights but no ownership. As time progressed, this system eventually disappeared.

We are discussing the character ‘虚’; previously, we talked about ‘丘’. The character ‘虚’ is composed of ‘虍’ (hū, meaning: tiger stripes) and ‘丘’. ‘虍’ indicates pronunciation, while ‘丘’ indicates meaning. Today, we have added the ‘土’ (tǔ, meaning: earth) radical to the character indicating a large earth mound, writing it as ‘墟’ (xū).

Input

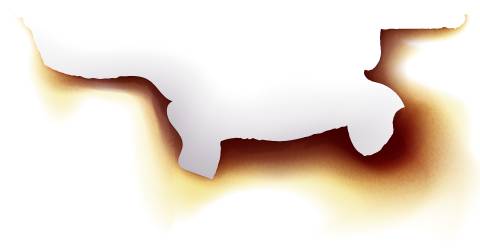

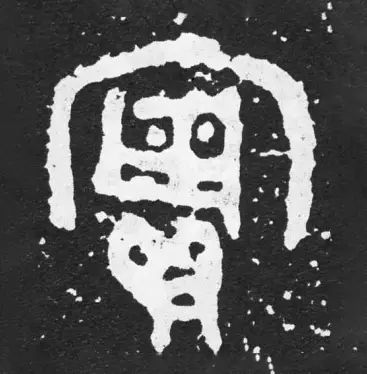

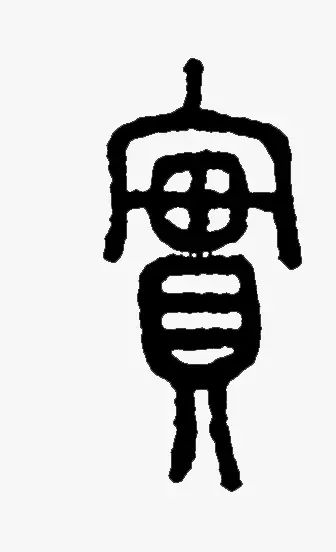

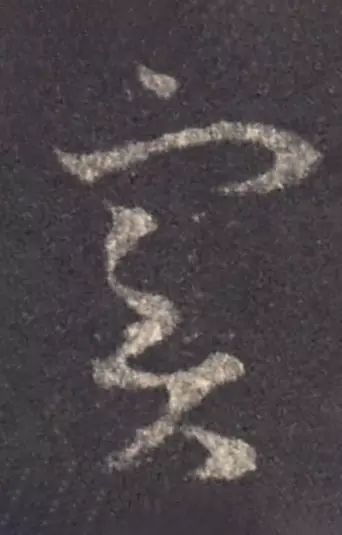

In the small seal script, ‘虚’ can clearly be seen as ‘虍+丘’.

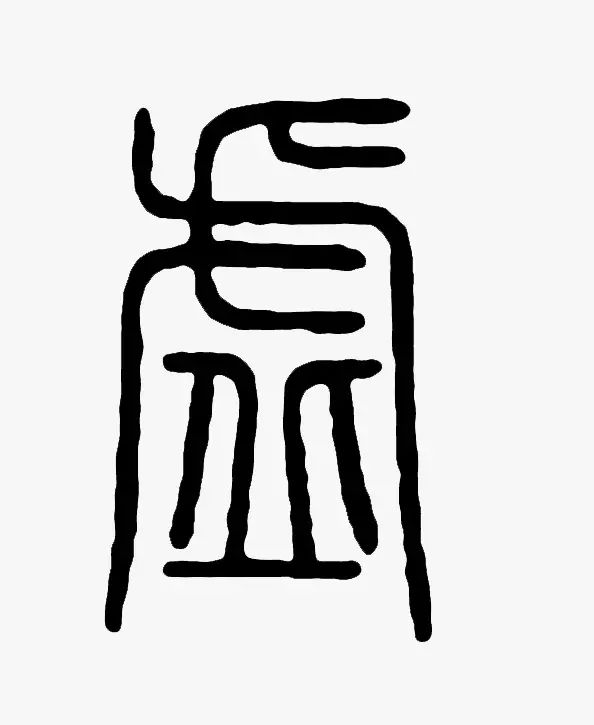

In the ‘Huashan Temple Stele’, the character ‘虚’ has the upper part ‘虍’ recognizable, while the lower part is the pictogram ‘丘’, represented by a horizontal line with two small earth mounds. This character was later miswritten as ‘业’ (yè).

Input

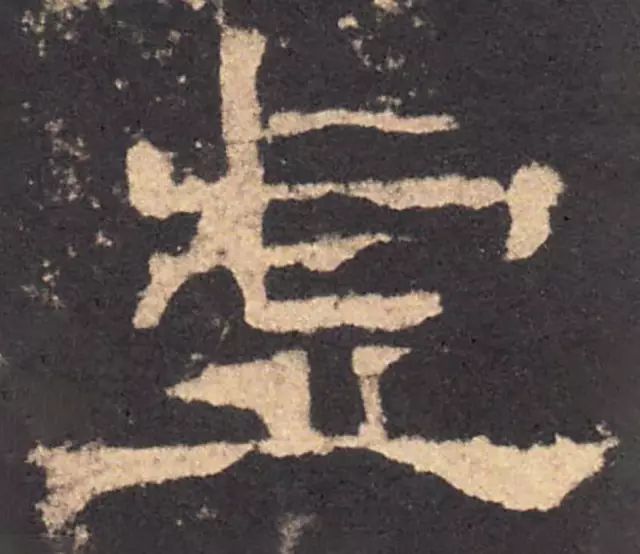

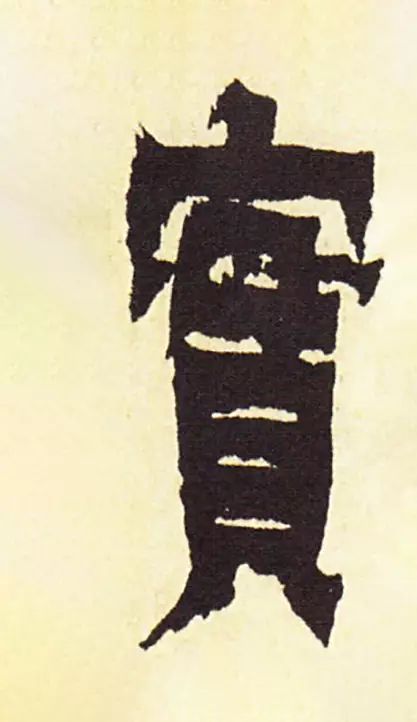

In the Wei stele,

‘虚’ is written with the lower part as ‘丘’.

Input

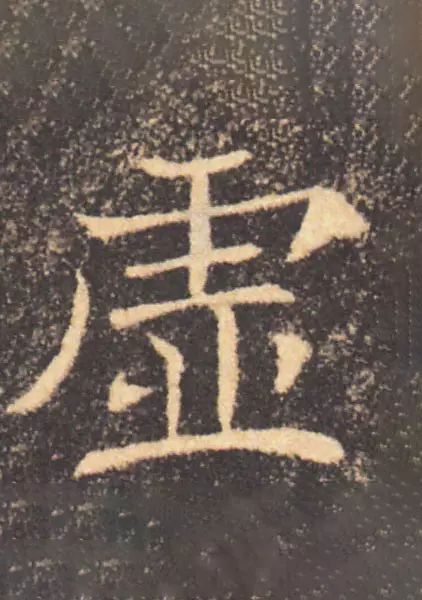

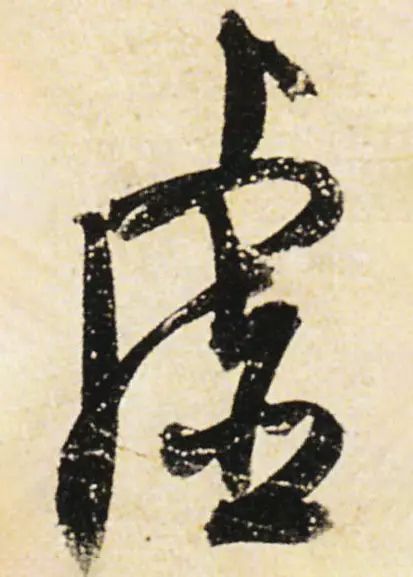

In the strokes of Chu Suiliang,

although they are finer, the character’s aura is very strong.

Input

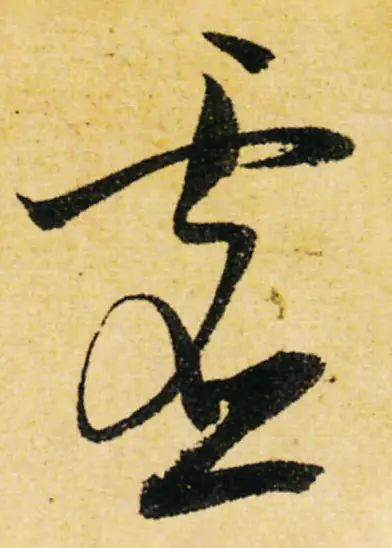

In the ‘Lanting Xu’,

‘虚’ is written with a sense of emptiness.

These two cursive scripts were written by two poets, one is Du Mu and the other is Lu You.

实

‘实’ (Shí) means wealth. It is composed of ‘宀’ (mián, meaning: roof) and ‘贯’ (guàn, meaning: goods and money). (from Shuōwén Jiězì) ‘实’ signifies affluence. The upper part is a ‘宀’ representing a house, and the lower part ‘贯’ represents goods and money. A house filled with goods and money is certainly wealthy, and this kind of ‘实’ is referred to as ‘家境殷实’ (jiājìng yīnshí).

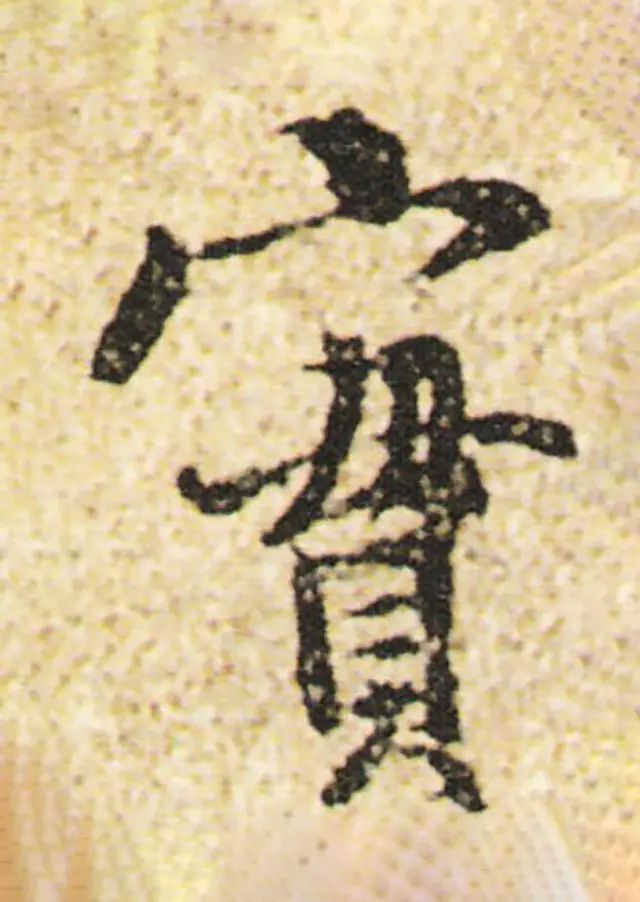

In the ‘San Shi Pan’, the character ‘实’ has ‘宀’ below, but instead of ‘贯’, it is ‘田+贝’, which essentially means the same thing. ‘田’ (tián) refers to land, now called real estate, and ‘贝’ (bèi) refers to money. It still conveys a sense of wealth. In bronze inscriptions, there are instances where the lower part is written as ‘贯’.

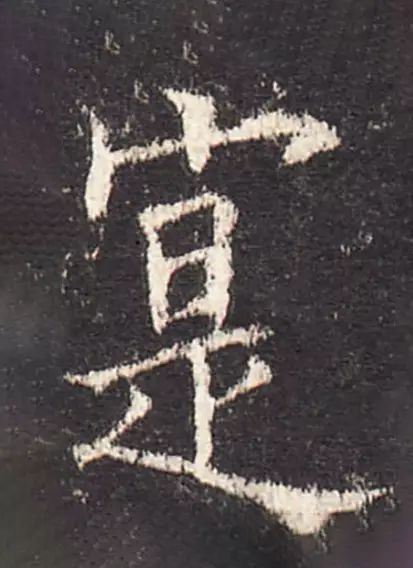

In small seal script, it is written as ‘宀+贯’.

Input 12

Jin Nong’s ‘实’ is written solidly, with the lower part ‘贯’ depicting ‘家财万贯’ (jiācái wàn guàn).

Input 12

The variant of ‘实’ is written as ‘宀+是’.

Input 12

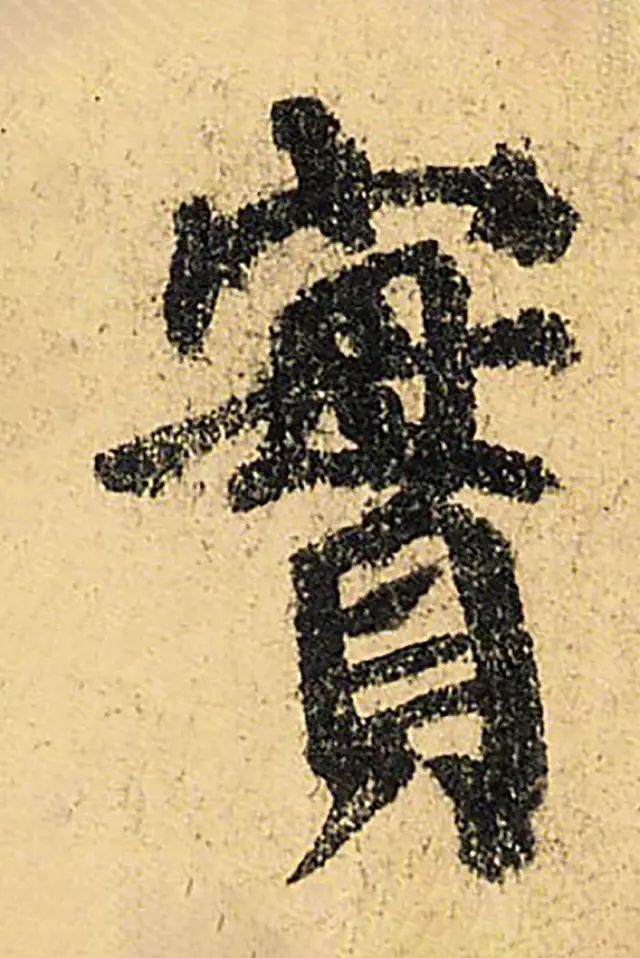

Yan Zhenqing’s ‘实’ has the upper part upright, while the lower part is slightly tilted to the left, giving the entire character a sense of solidity with dynamic movement.

Input 12

In the ‘Jiu Hua Tie’, the ‘实’ has ‘宀’ distanced from the lower part, leaving a large blank space, yet it does not appear empty.

Input 12

The cursive ‘实’ transforms the ‘贯’ part into a cursive style, resembling the character ‘头’ (tóu), and today’s simplified character ‘实’ derives from this.

Input 12

‘虚’ signifies a large earth mound, which implies emptiness and vastness. Something unreal is termed false or hypocritical, which is detestable, while humility and modesty are highly respected.

‘实’ signifies abundance. It is often used to describe fullness and substantiality. It also expresses sincerity and genuine intentions, and refers to fruits.

Having discussed the characters ‘虚’ and ‘实’, I must admit that my insights into the concept of ‘虚’ and ‘实’ in calligraphy are difficult to articulate. It’s not that I lack sincerity; rather, discussing such matters makes me feel somewhat insincere.

Author of this article

本堂

Born in 1987

Member of the Chinese Calligraphers Association, member of the Tianjin Artists Association

Member of the Tianjin Seal Carving Society, currently employed at the Cultural Center of Jinnan District, Tianjin.