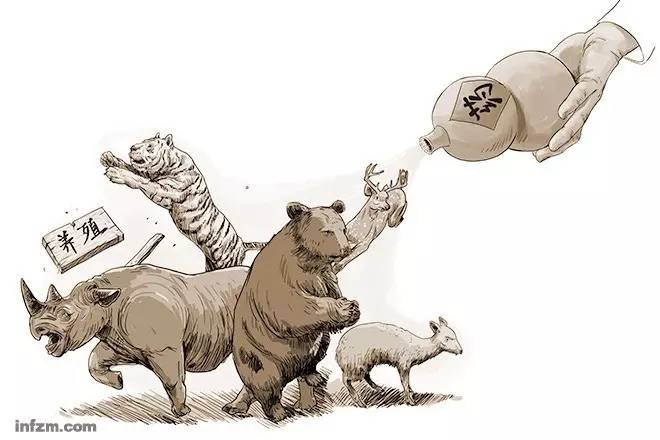

▲ New laws encourage the development of artificial cultivation and breeding, supporting the breeding and related research of precious and endangered medicinal wild animals and plants, while animal protection organizations worry about opening the floodgates for large-scale use. (Nongjian/Picture)

▲ New laws encourage the development of artificial cultivation and breeding, supporting the breeding and related research of precious and endangered medicinal wild animals and plants, while animal protection organizations worry about opening the floodgates for large-scale use. (Nongjian/Picture)

The Wildlife Protection Law has undergone its first major revision in 27 years, supporting the use of wildlife products in medicine. Many animal protection advocates are concerned, “Will this stimulate market demand and open the floodgates for large-scale use?”

Research conclusions in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) suggest, “The replacement of wild animal materials leads to a decrease in the efficacy and effects of traditional Chinese medicine.”

This article was first published in Southern Weekend

WeChat ID: nanfangzhoumo

“This is not an era for protecting wild animals.” On July 2, 2016, Zhang Xiaohai, Executive Secretary-General of the Beijing Aita Animal Protection Public Welfare Foundation (hereinafter referred to as “Aita Foundation”), lamented in a social media post. Just hours earlier, the newly revised Wildlife Protection Law (hereinafter referred to as “Wildlife Protection Law”) was passed by the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, marking its first major revision in 27 years. Regarding whether wildlife products can be used in medicine, the new law stipulates: Nationally protected wild animals with mature and stable artificial breeding technology can be sold and utilized with special identification after scientific verification. The use of wildlife and their products as medicines must also comply with relevant drug management laws and regulations. Previously, the draft of the TCM Law proposed, “Encouraging the development of artificial cultivation and breeding, supporting the breeding and related research of precious and endangered medicinal wild animals and plants.” The two laws echo each other, leaving a legal pathway for the use of wildlife in medicine. “Will this stimulate market demand and open the floodgates for large-scale use?” Like Zhang Xiaohai, many animal protection and scientific community members are concerned. “Whether wildlife can be used in medicine is the most controversial topic in the legislative revision.” At a press conference held after the revision, Zhai Yong, Director of the Legislative Affairs Office of the National People’s Congress Environmental and Resource Protection Committee, admitted. However, he also presented the conclusions of TCM research, “The replacement of wild animal materials leads to a decrease in the efficacy and effects of traditional Chinese medicine. If all wild animal materials are replaced in the future, traditional Chinese medicine may become ineffective.” Rhino horn, tiger bone, musk, cow bile, bear bile powder… As TCM faces an increasingly depleted resource of medicinal animals, the dilemma of whether to protect animals or continue to treat and save lives has become a pressing issue. 1 Early Cancellation of Some Rare Animals in Medicine If it weren’t for the ban in 1993, Chen Shu (pseudonym) might have had a promising financial outlook for his tiger breeding farm. Now, the wealth worth over 100 million yuan—adult tiger carcasses—can only lie dormant in cold storage, becoming a heavy burden for the breeding farm. On May 29, 1993, due to the situation where there were fewer than 100 wild tigers in the country, the State Council issued a notice prohibiting the trade of rhino horn and tiger bone, halting all trade activities related to tiger bone domestically. The former Ministry of Health removed the medicinal standards for tiger bone from the “Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China,” and all traditional Chinese medicine products related to tiger bone were discontinued. Previously, China joined the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora in 1980, strictly prohibiting the international trade of tiger products. “I was completely stunned,” Chen Shu said. Originally, the breeding farm had hoped that once the tiger population reached a certain number, they could consider using normally deceased tigers in medicine. They had just overcome the technical challenges of artificial breeding, and the number of tigers was increasing day by day, but before they could celebrate, they were hit with a heavy blow. The policy change left the breeding farm in a difficult position. A three-year-old tiger consumes eight kilograms of meat a day, costing tens of thousands of yuan a year just for food. The huge funding gap for raising tigers forced the farm to reduce feeding amounts, switching to cheaper chicken instead of beef. An animal protection advocate revealed that some breeding farms even fed tigers chicken necks and heads, which they disliked, leading to the once-mighty “mountain king” becoming severely malnourished and resembling a “sick cat.” The ongoing ban on tiger products has rendered naturally deceased adult tigers worthless. Over the years, the breeding farm where Chen Shu works has never stopped lobbying for the lifting of the tiger trade ban. He spends hundreds of thousands of yuan annually to maintain the frozen tiger carcasses, hoping for the day when this potential wealth can be “monetized.” “This is a dangerous gamble,” Chen Shu hopes that one day, these deceased tigers can openly “leave” the cold storage. The pressure of survival behind “raising tigers for profit” is compounded by the frequent alerts regarding the medicinal sources from wild animals, forcing the state to tighten management of TCM materials involving endangered and rare animals. In 1987, the State Council issued the “Regulations on the Protection and Management of Wild Medicinal Material Resources,” involving 14 types of endangered and rare animal medicines. Among them, four types involving first-level protected wild animals, such as tiger bone, leopard bone, and rhino horn, are prohibited from hunting and are subject to natural elimination, with their medicinal parts managed by various levels of medicinal material companies. Ten types involving second-level protected wild animals, such as deer antler (Cervus nippon), musk, bear bile, pangolin, toad oil, and others, are required to limit usage; animals like antelope and snakes with medicinal effects are strictly managed and protected. Because of this, the “Compendium of Materia Medica” recorded 461 types of animal medicines, while this number sharply decreased to about 50 in the “Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China.” However, within the TCM community, calls to restore the use of some precious animals in medicine have never ceased. “Can the bones of normally deceased artificially bred Northeast tigers be considered for medicinal use?” Li Lianda, an academician of the Chinese Academy of Engineering and a pharmacologist of traditional Chinese medicine, supports the use of wild animals in medicine from the perspective of medicinal demand—tiger bone has irreplaceable effects in bone healing and muscle recovery. “In the past, excellent TCM products made from tiger bone for treating osteoporosis and rheumatoid arthritis are now almost all stagnant.” Li Lianda told Southern Weekend reporters that although the application range of animal medicines is not as broad as that of plant medicines, it has a history of over two thousand years, and some are even irreplaceable for treating critical conditions. For example, bear bile has been used in the treatment of infectious diseases, heart, brain, liver, kidney, and tumors, resulting in over 150 types of TCM products. National Committee member and Director of Orthopedics at the Beijing Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Wen Jianmin, has even raised the restoration of precious animals in medicine to the level of “the survival of traditional Chinese medicine,” stating, “The early cancellation of some medicinal animals’ breeding and use has led to the loss and distortion of many traditional famous prescriptions and medicines. If we do not protect them well, famous medicines like musk, bear bile powder, and cow bile will be completely exterminated, and traditional Chinese medicine will exist in name only.” 2 Development of Artificial Breeding or Artificial Alternatives? There is demand, but little or no supply, leading the TCM community to turn its attention to artificial breeding. “The development and utilization of animals in medicine do not contradict animal protection,” Li Lianda emphasized, stating that the Wildlife Protection Law targets “wild animals” and should not be confused with artificial breeding. Reasonable development and utilization can effectively protect wild animal resources. The wild sika deer is a rare and endangered species, only allowed for protection, not for consumption or medicinal use. However, the number of artificially bred sika deer in the country has increased to over ten thousand, “benefiting patients, promoting special economic development, and preventing species extinction—why not utilize them reasonably and in a controlled manner?” In Li Lianda’s view, the passive protection model of “no one can touch” seen abroad has proven ineffective, with the number of extinct species increasing year by year. However, animal protection and scientific communities insist that seeking alternatives to rare natural animal medicines is the best way to solve the shortage of animal medicine sources. “Since there are already artificial alternatives, why still use wild animals in medicine?” In January of this year, the “Research and Industrialization of Artificial Musk” won the National Science and Technology Progress Award for 2015. According to data from the National Food and Drug Administration, there are currently 760 companies in China producing and selling 433 types of TCM products containing musk, of which 431 have completely replaced natural musk with artificial musk. It is estimated that the use of artificial musk has resulted in the reduction of hunting 26 million natural musk deer. “A 99% replacement rate is not achieved overnight.” One of the project participants, Yan Chongping, recalled that although artificial musk has performed excellently in various aspects and has undergone authoritative verification, when it was established as a new type of TCM in 1994, many “old masters” in the TCM community found it difficult to accept due to long-standing beliefs. Over the past 20 years, the resources of musk have become increasingly scarce. The production process of artificial musk has continuously improved, and its effectiveness has withstood more and more tests, becoming an important raw material for many national treasure-level TCM products such as Six God Pills, An Gong Niu Huang Pills, and Musk Heart Preserving Pills. However, to this day, the mainstream view in the TCM community still holds that most natural animal medicine alternatives have not achieved breakthroughs. “If there is a natural option, we should use it as much as possible; this viewpoint must be upheld,” said Zhou Chaofan, a researcher at the Chinese Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Currently, there are generally two methods for replacing natural animal medicines: one is to use similar natural animals as substitutes, for example, TCM products containing rhino horn often use water buffalo horn as a substitute. The other method is to replace it with artificially synthesized non-natural products. “Whether through similar substitution or artificial synthesis, the common issue is that equivalence cannot be achieved.” Li Lianda cited the example of bear bile, stating that the natural components of bear bile include five major categories, including bile acids, while artificial bear bile only contains “ursodeoxycholic acid,” which is just one type of bile acid and cannot fully replace the medicinal effects of natural bear bile. In fact, German ursodeoxycholic acid capsules (Ursodeoxycholic acid) and Italian taurine ursodeoxycholic acid capsules (Taurine) have already been marketed in China, with annual sales reaching billions of dollars. What puzzles Li Lianda is that in 2004, the state removed “bear bile capsules” from the “National Essential Medicines List” but included Germany’s “ursodeoxycholic acid capsules” in the “National Medical Insurance List.” Japan produces a heart-saving pill based on ancient Chinese formulas, containing bear bile, musk, cow bile, toad, and other rare TCM ingredients, which can be sold globally without hindrance, with sales reaching hundreds of billions; while similar medicines produced in China face bans on export and domestic sales. “Why is it that foreign TCM products can enter China without opposition, while domestic similar TCM products face numerous obstacles?” Li Lianda questioned, suggesting that behind the opposition to the use of wild animals in medicine by animal protection organizations, there are “other factors.” Similar views have many supporters in the TCM community. Chen Qiguang, head of the major research project “National Conditions Research on Traditional Chinese Medicine,” believes that there is a competitive relationship between TCM and Western medicine, stating, “The development of TCM has hindered the interests of Western medicine.” “Some views in the TCM community mislead the public and even officials,” said Sun Quanhui, a senior scientific advisor at the World Animal Protection Association, emphasizing that it is precisely the use of a few endangered wild animals in medicine that has damaged the reputation of TCM internationally and hindered its better integration into the world. 3 Artificial Breeding Does Not Help Wild Species Protection The sharp contrast between the TCM community and animal protection organizations highlights the conflict between the TCM industry and animal protection regulations. In 2008, Meng Zhibin, a researcher at the Institute of Zoology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, conducted a preliminary survey of the wild resource status of 112 commonly used medicinal materials, finding that 22% were listed as endangered species, with 51% being endangered. Among medicinal animals, the proportion of endangered species is as high as 30%. “The artificial breeding of wild animals contributes very little to the protection of wild populations,” said Xie Yan, an associate researcher at the Institute of Zoology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and director of the China Program of the International Wildlife Conservation Society. Black bears, Northeast tigers, and red-crowned cranes are all “star species” of artificial breeding, but studies show that the number of these species in the wild continues to decline. Animal protection experts worry that the strong demand for wildlife in medicine will stimulate market consumption and encourage poaching of endangered species in the wild. In the memory of Park Zhengji, a researcher at the Changbai Mountain Academy, he used to see groups of black bears frequently. However, since the late 1980s, such warm scenes of wild black bears have almost disappeared. Park Zhengji has been engaged in wildlife protection research in the Changbai Mountain Nature Reserve since 1977. A study conducted by his team showed that from 1986 to 2015, the number of black bears in the Changbai Mountain Nature Reserve decreased by 90%.

“This period coincided with the rapid development of the bear farming industry and the rise of live bear bile extraction,” he said, noting that the price of bear bile soared to over 100 yuan per gram, and the growing demand combined with profit motives led to increased poaching, which was one of the significant reasons for the decline in wild populations.

▲ Black bears at the Guizhen Tang breeding base. (Dongfang IC/Picture)

The wilding of artificially bred populations is not easy. Park Zhengji’s team once released five captive black bears, but the wild population did not accept them, stating, “They have basically been naturally eliminated and can only seek food in residential areas.” Currently, the artificial breeding technology for black bears is relatively stable, but the wild population of black bears in the country does not exceed 20,000. In 2012, the Asian black bear was listed as “vulnerable” in the Red List of Threatened Species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. What worries animal protection experts even more is the TCM community’s concept of “developing first and protecting later”—setting up numerous research and artificial breeding projects to save already endangered species, while taking few effective measures to prevent currently abundant species from becoming endangered.

The most ironic example is the process of endangerment of the saiga antelope. In 1988, China listed the saiga antelope as a first-level protected rare animal nearing extinction, but at that time, Mongolia and Kazakhstan still had over 1 million individuals. The World Wildlife Fund called on TCM pharmacists to use antelope horn as a substitute for rhino horn. However, by 1995, the World Wildlife Fund had to stop this promotion because the entire population of saiga antelope was listed in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, and they themselves became endangered animals.

▲ Saiga antelope (Xinhua News Agency/Picture)

“In 2000, the global population of saiga antelope in the wild was close to 180,000, but by 2002, it sharply decreased to 50,000.” Joint statistical data published in the journal Nature by institutions such as Cambridge University and Imperial College London revealed that the sharp decline was due to poaching by Russian poachers to meet the demand for traditional Chinese medicine after the trade opened along the China-Russia border.

East China Normal University doctoral student Kang Aili also conducted statistics, revealing that between 2000 and 2002, the publicly reported amount of smuggled saiga antelope horn in China came from at least 14,867 killed saiga antelopes. This means that in the two years, at least 10% of the saiga antelopes that disappeared were seized in China, and the amount of smuggling not seized could far exceed this number. “If this trend continues, the continued increase in endangered species involved in TCM will be inevitable,” Meng Zhibin warned. 4 The “List” Awaiting Revision The new Wildlife Protection Law has been finalized, and the disappointed animal protection community has placed its last hope on the revision of the “List.” Article 28 of the Wildlife Protection Law stipulates: For nationally protected wild animals with mature and stable artificial breeding technology, after scientific verification, they will be included in the “List of Nationally Protected Wild Animals for Artificial Breeding” formulated by the State Council’s wildlife protection authority. Wild animals and their products included in the list can be sold and utilized with an artificial breeding license and special identification. In addition, for artificially bred populations of wild animals with mature and stable breeding technology, once the protection status of the wild population is good, they may no longer be included in the “List of Nationally Protected Wild Animals” and will be managed differently from wild populations. “Populations with mature artificial breeding technology may be managed like livestock and farm animals in the future.” Although there is hope that the “List” will be strictly managed in a public welfare direction, Zhang Xiaohai is not optimistic when recalling the statement in the draft of the TCM Law that “supports the breeding of precious and endangered medicinal wild animals.” He analyzes that for the TCM industry to develop, the national essence needs to be inherited, and the common demand will likely form an alliance between the industry and government authorities. The economic strength of the industry is substantial, and the authorities control government resources, meaning that “the voice of the industry is likely to be amplified.” According to regulations, pharmaceutical companies using terrestrial wild animals and their products as raw materials must affix the “Special Identification for the Management and Utilization of Wild Animals in China” issued by the forestry department on their product packaging. The disputes of interests between departments also bring variables to the revision of the list. An industry insider revealed that as early as the 1990s, there were proposals to revise the Wildlife Protection Law and the list of nationally protected wild animals, but “the power struggles between departments, or the ownership disputes over wild animals, have stifled the demand for legislative revision.” In China, terrestrial and aquatic wild animals are managed by the forestry and agricultural departments, respectively, making it difficult to distinguish whether some wild animals are terrestrial or aquatic. “If you say this is terrestrial, and I say this is aquatic, what should we do if the two departments cannot agree? We can only drop it.” The aforementioned insider had proposed that the agricultural and forestry departments each propose a list of key protected wild animals, to be decided by an intermediary agency, and suggested the establishment of a dedicated wildlife management department to avoid disputes. However, ultimately, none of the proposals were adopted, as “the modification of laws means a redistribution of power, and ultimately, some departments are unwilling to relinquish power.” According to Fan Zhiyong, senior director and chief researcher at the World Wildlife Fund, the Wildlife Protection Law belongs to the category of resource law, and thus, the issue of utilization cannot be avoided. The World Wildlife Fund has always advocated that the reasonable use of wildlife resources will minimize the impact on wild populations. “All decisions should be based on scientific, rational, and sustainable principles,” Fan Zhiyong believes that if biodiversity conservation is prioritized, humanity should make appropriate concessions. “If we are unwilling to give up anything, will both humans and all wild animals perish?” Related Content

Related Content

Although enterprises operate legally and compliantly, Guizhen Tang is still rejected by the capital market. Behind this lies the opposition between rare animal protection and TCM strategy. Although the outcome is unknown, conspiracy theories have already emerged.

Click the blue text,to read:“Guizhen Tang’s Awkward Path to Listing“.